Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

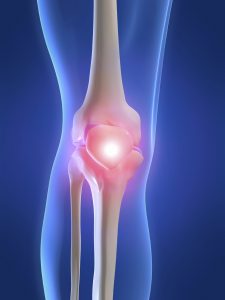

One of the biggest challenges for clients overcoming knee injuries and surgery is regaining their quadriceps strength and fighting atrophy. This is increasingly so for my clientele on crutches for any extended period of time. It is paramount to use modalities early on in the rehab process such as electrical stimulation and blood flow restriction training to combat atrophy and loss of strength.

Once appropriate, I always move to single limb training to eliminate imbalance and asymmetry. While pistol squats are one of the most effective single leg quadriceps exercises, not all clients can perform this movement. So, in many cases I opt to use a single leg box squat (see video below).

For more information on specific progressions and regressions, click here to read my entire online column. Keep in mind that you should never force through any painful range of motion as this likely indicates excessive strain on the patellofemoral joint.

Knee pain is prevalent among adolescents and active adults. Patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis are the most likely causes of pain. It may be present with squatting, lunging, prolonged sitting, kneeling, running, jumping or twisting.

Research seems to support a combination of hip and knee strengthening as a primary line of defense and treatment for knee pain. Interestingly, males with PFP do not seem to have weakness in the gluteus medusa like their female counterparts. The link below is an abstract that speaks to this difference between the two groups:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30090674

Other modalities used to address anterior knee pain include patellar bracing/taping, blood flow restriction training, dry needling/acupuncture and soft tissue work seems to bring more questions accordion to some experts.

Click here to read the 2018 Consensus statement on exercise therapy and physical interventions (orthoses, taping and manual therapy) to treat patellofemoral pain from the 5th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat.

Clinically, I have seen good results with the following:

1. Activity modification

2. Glute and quadriceps strengthening

3. Blood flow restriction (BFR) training

4. Sequential and progressive loading based on pain response

In the majority of patients I see with knee pain or knee dysfunction, I uncover gluteal weakness and poor proximal muscular stability. This can cascade into overpronation, vagus collapse, poor balance, and any number of kinetic chain issues. While this may not be a big deal for sedentary individuals, it becomes a very big deal for athletes and those performing repetitive loading.

When searching for the best exercises to selectively strengthen the gluteal muscles, it is always wise to see what science has to say. More is not always better. I am all for efficiency and finding the most effective exercises in activating the glute over the tensor fascia lata (TFL). In this post, I am sharing a good exercise to do just that. Prior research has indicated that sidestepping and clamshells are very effective in doing just this. Click here to read a prior post on this.

The video below will walk you through his to do the running man exercise.

Click here to read my PFP column on this exercise.

Improving proximal hip stability and reducing frontal plane collapse is critical for protecting the knee. Poor frontal plane control often contributes to anterior knee pain, IT band syndrome, shin splints, plantar fasciitis and other injuries. This exercise is an advance progression of the standing pallof press, and it is very effective for enhancing single leg strength as well as hip/core stability.

Click here to read my full column on this exercise in PFP Magazine.

Unfortunately, too many athletes who recover from ACL tears go on to suffer another injury within a short period of time. Click here to read a prior post on secondary injuries. There are differing opinions on when or if there is an exactly “right time” to clear an athlete for return to play.

We already know that athletes have persistent weakness and asymmetry at 1 year post-op and even beyond. I recently had one of my collegiate soccer players re-tear while helping out with a youth soccer camp. She had not yet done hop testing with me or been cleared for full soccer, but as she was 1 year out she did not think it would be an issue playing with 12 year-old girls. It only took 20 minutes before she suffered a non-contact re-injury and lateral meniscus tear.

Consider the following paper that reveals low rates of patients meeting return to sport (RTS) criteria at 9 months post-op:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29574548

Another paper recent published in the Journal of Sports Rehabilitation revealed marked deficits in balance and hop testing at 6 and 9 months post-op:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29466066

A recent paper in the American Journal of Sports Medicine (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29659299) lists positive predictors of a return to knee-strenuous sport 1 year after ACL reconstruction were male sex, younger age, a high preinjury level of physical activity, and the absence of concomitant injuries to the medial collateral ligament and meniscus.

In 2016, research in the American Journal of Sports Medicine revealed delaying return to sport at least 9 months markedly reduced re-injury risk in those who passed RTS testing. Click below for more on that study:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27162233

So, where are we now? I employ multiple functional tests including the Y-Balance Test, FMS, single leg squatting, hand held dynamometry, hop testing, qualitative movement assessment and jump landing assessments. But, is that enough?