Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Shoulder impingement and scapular dysfunction are common issues that plague many clients. Research indicates that certain muscles tend to dominate others while other muscles fatigue easily leading to faulty movement patterns and increasing the risk for impingement. Muscle length and posture are also key factors to consider.

I like to use a mini-band retraction with clients exhibiting excessive scapular abduction. In the video below, you will see a simple, yet effective exercise to address this faulty alignment of the scapula. Keep in mind, you must observe the client or patient from behind with the scapula exposed to properly assess alignment and movement.

This exercise is designed to strengthen the middle trapezius and rhomboids. In addition, it will improve scapular stability. Scapular abduction is usually more evident with elevation from 90-180 degrees as the ratio of scapular movement to glenohumeral movement is 1:1 instead of the normal 1:2 ratio throughout since the scapula is already in an excessively abducted posture at rest.

To read more on the application and exact execution of this exercise, click here to read my column for PFP Magazine.

Through my clinical practice and sports performance training, I continue to focus on eliminating core and hip dysfunction. I think many of the knee problems I see in runners and females are related to weakness in the glutes and small lateral rotators. There has also been quite a buzz about a recent article written in the Strength & Conditioning Journal on crunches and whether spinal flexion may actually be good for you.

This topic alone could take up several posts so, I will not delve into that today. However, as one who has experienced sciatica and disc injury firsthand, I probably tend to fall a little more in the camp of focusing on a neutral spine and resisting external forces as I feel this helps improve performance and reduce injury risk. In that vain, I have been continuing to develop my own core and hip stability progressions with my advanced clients/athletes.

I have been doing a series of posts for BOSU and PFP in my Functionally Fit Column. In my last post, I covered a 3D mountian climber with hip extension. In today’s post, I am covering a great core exercise with the BOSU Ballast Ball focusing on hip extension with the goal of improving shoulder, core and hip stability while promoting hip extension and disassociation.

In the video below you can check out the progressions (incline and decline)

Click here to read the full article on technique and application. The article reviews a regression for those not ready to tackle this quite yet. I think you will find this exercise challenging and rewarding.

I have had the pleasure of authoring a bi-weekly column for PFP’s online magazine entitled “Functionally Fit” for over three years now. This column gives me a creative avenue to display my specific training techniques and teach others how to build a better functional body in the process.

One of the greatest things about exercise is all the different options, variations and tweaks available to bring about a desired physical change in the human body. As Alwyn Cosgrove once said, “Exercise is like medicine.” By this, he means the right dosage and application is critical. I could not agree more.

As training and rehab continue to evolve and become even more intertwined, we as practitioners need to continue seeking ways to get more from our exercises. I personally use lots of different training tools in my trade, but I am always seeking to get the biggest return on my exercise investments. Today, I am sharing one such exercise with you, the 3D Mountain Climber with Hip Extension. Check out the video below:

In this video, I am working to improve shoulder, hip and core stability as well as strongly encourage hip disassociation. Many clients I train and rehab simply are asymmetrical or cannot disassociate their hips which leads to flawed movement patterns and leaks int he kinetic chain.

I used this exercise in our core training series we were doing with the Carolina Hurricanes in their pre-season conditioning sessions that we just recently completed. It is not easy, but delivers so much benefit for just one movement. In the video I display a BOSU balance trainer, but in my online column for PFP, I include a full buildup progression as well. Click here to read the column.

This post is a follow-up post to one of my previous ones, A Closer Look at Push-ups & Modified Push-ups, based on some dialogue with a reader. Click the link to familiarize yourself with the background. Some people simply do not agree with my assertion that modifying and or limiting end range of motion with certain exercises such as bench press, push-ups and flies is needed to preserve shoulder health long term.

So many people want to hitch their wagon to “simply strengthen the scapula” as a fix all solution. While I agree 100% that scapular stabilizer and cuff strengthening goes a long way, we would be foolish to ignore joint biomechanics, physics and kinesiology when examining how loads affect joint structure and function over time.

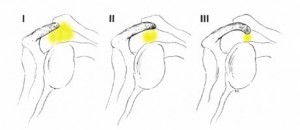

I will start out by saying I ascribe to the idea that a healthy joint should be able to move through full range of motion. My question to you is with how much load and how many times over and over again before destructive microtrauma sets in. With that said, how many healthy shoulder joints do you think are working out in gyms across the world today? Without an x-ray, it is impossible to know if you have a type I (normal), II (flat) or III (hook-shaped) acromion. Your genetics do make a difference in your risk for developing shoulder problems, as types II and III are more prone to impingement (see photos below)

This is one risk factor that cannot be mitigated by prehab if you will. I would also challenge you to consider that loading the shoulder repetitively with heavy loads in the furthest depths of shoulder horizontal abduction (bar touching the chest in bench press or lowering DB’s well below the plane of the body with flies) will eventually create atraumatic shoulder pathology.

Ever wonder about things like:

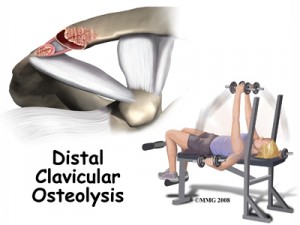

- Osteolysis of the distal clavicle

- Anterior shoulder laxity (over stretching the anterior capsule and joint structures over time)

- Creating impingement with repetitive motion in the presence of poor bony architecture, a thickened bursa or inadequate shoulder stability

While some may argue lifting does not create instability (it is known that bench press may lead to subtle posterior instability over time), I don’t think we can question the impact of weight lifting on clavicle destruction. Men more commonly develop acromio-clavicular arthritis, and osteolysis of the clavicle is common with lifting exercises such as bench press, dips and upright rows.

Click here for an article discussing osteolysis of the clavicle. The authors specifically mention modifying or avoiding certain weight lifting techniques base on pain and radiographic findings. I think we must as fitness professionals, strength coaches and educators look at the long term implications of lifting techniques on long term shoulder health and function.

Most would not hesitate to say they would do anything to avoid shoulder surgery if they knew their exercise habits might pose a risk for a future procedure to alleviate pain and restore function. I firmly believe avid recreational weight lifters and bodybuilders should modify range of motion with many of these pressing and lifting motions to be safe. This includes blocking full range bench press, modifying flies and push-ups, avoiding deep dips and generally minimizing how often they choose to do dips and upright rows. I also feel most people over age 35 or 40 should minimize the frequency of dips and upright rows as risk outweighs reward over time with repetitive loading of the clavicle (particularly if they have a long history of weight lifting already).

Take a look at the x-ray below showing osteolysis. You can often see a widening at the AC joint. Many times, these patients must undergo steroid injections, rest, activity modification and even a distal clavicle excision to resolve the pain.

Call me conservative or crazy, but I know personally how limiting bench press/fly range of motion eliminated my cuff pain in less than 2 weeks years ago when I was in college. Additionally, I currently have two patients in my clinic with shoulder injuries:

- A 19 y/o male hurt doing submax loads full range with a barbell

- A 60 plus y/o male who had arthroscopic repair of a torn supraspinatus that occurred while doing dumbbell flies (submax loads) on a flat bench lowering the dumbbells far below the parallel

Two patients decades apart hurt by the same mechanism – a biomechanical mismatch and repetitive microtrauma. So, my own body, years of clinical and training experience, and research studies have led me to conclude that modifications for those choosing to do resistance training 2-3 plus times per week for many years on end are necessary to have healthy shoulders for years to come. If you value your shoulder health and that of your clients, consider restricting depth, reducing shoulder abduction angels with pressing and carefully selecting and or limiting certain exercises based on client medical history and functional goals.

By far the most comments on my blog and emails that flood my inbox these days have to do with SLAP tears. I must admit that outside of ACL tears and rotator cuff issues, I find myself increasingly drawn to studying and researching this issue. It definitely is a source of great pain for many and an issue that medical professionals are challenged by today.

In my personal clinical experience, I see good, bad and in between outcomes. Through email and my blog I tend to read more on the not so good side from people who are seeking my expertise in how to resolve their issues. When I speak to surgeons, I find they are often hesitant to commit to a set algorithm of treatment, and they are not 100% sure what the right answer is in addressing these injuries as a whole.

If you read the literature, the success in terms of patient satisfaction and return to premorbid activity levels is not going to make you rush down to the operating room and opt for an arthroscopic repair if you are an overhead athlete (especially baseball players). However, other studies have presented more favorable data ranging from 63%-75% good-excellent satisfaction in other overhead athletes who have had the procedure done.

If you are unfamiliar with SLAP tears, I suggest reading my original post on them (click here). In today’s post, I wanted to present a quick recap on Type II SLAP tears and some new published research on the results of revision procedures where the primary repair failed.

Below are two images of a type II tear (MRI and operative view from the scope)

Keep in mind a type II tear means the biceps anchor/superior labrum has pulled away from the glenoid with resulting instability of the complex. This is the most common type of tear seen among injured people. In a study from the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in LA in the latest American Journal of Sports Medicine (June 2011 – click here for the abstract), they discussed a chart review of from 2003-2009 looking at patients who had undergone revision type II SLAP repairs.