Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

There seems to be consistent questions, debate and studies done with respect to stretching. As the thought of more closely analyzing the quality of movement (FMS, Y-Balance testing, SFMA for example) moves to the forefront in the PT and fitness world, many search for the right mix of exercise to maximize mobility.

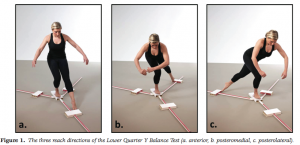

I count myself as a supporter and follower of the work of Gray Cook and Stuart McGill. While I may not agree 100% with all of their ideas, I generally consider them to be brilliant minds and ahead of the curve. I have been using the FMS in my practice for some time now and have also begun to incorporate Y-Balance testing as well (see pic below courtesy of the IJSPT)

The Y-Balance test may not have significant relevance to hip mobility as much as it does limb symmetry, but I included it here to illustrate my point in observing kinetic chain movement to help determine where the weak link or faulty movement pattern may be. It gives us valuable information with respect to strength, balance and mobility.

With the revelation that FAI is more prevalent than we knew (click here for my post on FAI), I am always interested in hip mobility and how to increase movement in the hip joint. Limitations in hip mobility can spell serious trouble for the lumbosacral region as well as the knee.

I currently use foam rolling, manual techniques, dynamic warm-up maneuvers, bodyweight single leg and hip/core disassociation exercises and static stretching to increase hip mobility. However, I am often faced with the question of what works best? Is less more? How can I make the greatest change without adding extra work and unnecessary steps?

Well, Stuart McGill and Janice Moreside just published a study in the May 2012 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research that sought to examine three different interventions and how they improve hip joint range of motion. Previous work has been focused on the hip joint alone, and they wanted to see how other interventions impacted the mobility of the hip. Click here for the abstract

I thought a fitting way to kick off the new year would be to share the top 10 things I learned or embraced that have most shpaed and impacted my training and rehab this past year. In no particular order I will rattle these things off. I hope at least one of these little pearls has a positive impact on your training and/or rehab as well.

- Often times it appears necessary to perform a biceps tenodesis or tenotomy in active adults undergoing a SLAP repair to ensure more predictable pain relief. I heard this at a sports medicine conference last May and I can tell you those patients having this done alongside their shoulder surgeries seem to recover quicker with less pain relief. With that said, keep in mind that SLAP tears are difficult to define and operate on as surgeons still do not have great agreement across the board on defining the extent of injuries and how to deal with them (operative vs. non-operative).

- Performance on the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) has little to no correlation with athletic performance. I screened an NBA player and an NFL player this year who both failed the screen. However, they obviously have mad athleticism and genetic ability. Keep in mind the FMS is a valuable tool used to assess movement and expose injury risk patterns based on the 7 tests.

- Soft tissue therapy is undervalued and misunderstood by most lay people. Assessing tissue restrictions and educating our clients to perform self myofascial release techniques is essential if they want to compete and remain healthy day in and day out. Specific problem areas I have increased my focus on this year have been the psoas, soleus and posterior rotator cuff/joint capsule. Click here for my soleus blog post.

- Core training is probably as much about not moving as it is about generating force with movement. I read work from Stuart McGill and other smart people in the field, and the concepts of anti-rotation and anti-extension are sound concepts to explore and look more closely at. Many times, performance in sport and life require us to resist movement and maintain position so strengthening the core to resist potentially harmful and stressful motions is and should be an important part of training and rehab programs. Understanding how to facilitate and activate core musculature in the training to protect the spine and improve mobility/strength is key. Click here for more on my core training.

- Hip dissociation is an important element to train as the lack of it can impact function and performance in a negative way. We assess it on the active SLR in FMS and I see the lack of it show up on clinical exams all the time. Whether it is HS tightness, hip flexor weakness or simply poor neuromuscular control, clients who are unable to effectively dissociate the hips are more prone to injury and limited performance.

Continue reading…

One of the most common PT clients I see is an injured runner. There can be a umber of different reasons or factors involved leading up to a running injury, but I wanted to focus on this idea of gait retraining that is taking place today. With the advent of Born to Run and minimalist footwear, people have begun to question and debate what the best way to run is.

Is this suited for everyone?

Let me just say right away that I do not believe there is a simple answer here. Human beings are all unique and have different genetic and biomechanical makeups. What this means in effect is that they have their own set of “issues” if you will that I classify into common categories such as:

- Static alignment problems (arch, knee, hip, etc)

- Static and dynamic balance deficits

- Inefficient gait mechanics

- Muscle imbalances

- Soft tissue tightness

- Recurring pain patterns

The list could go on and on, but you get the point. The idea of “re-teaching” someone how to run differently than their natural motor pattern dictates in not easy and is a decision that should be well thought out and based on sound decision making. We are pre-programmed at birth with certain native motor patterns and running is one of those patterns. Generally, your brain finds the most efficient way for you to run in your own body.

Now granted, some run much better than others. Perhaps we can say athleticism plays a role in this, but as we grow and reach skeletal maturity our body type, training experience, strength and environment are also major factors . With that said, I know that runners with recurrent and/or chronic pain are looking for a finite solution to their problem. They grow frustrated when they are unable to log all their miles or finish a race.

If traditional PT or relative rest fails to alleviate the pain, we must delve deeper and look more closely at their gait. I think video analysis is a great tool for doing this. We use Dartfish at my clinic, and this is very useful for breaking down gait mechanics and detecting things like heel versus forefoot striking, overpronation, asymmetry side-to-side, trunk inclination, etc. Once we find things on video we must also correlate these findings to our clinical screening to uncover a cause and effect relationship.

Eliminating the “false step” has been a personal mission of many strength coaches I have heard or worked alongside of in my 15 year career. I used to wonder quietly why it was such a bad thing early on in my coaching. Based on angles and observation it seemed almost reflexive for most athletes.

Then a few years ago I had the privilege of seeing Lee Taft present his theory on speed development and multi-directional speed training and it all came together for me. Lee eloquently explained that the “false step” is really just a plyo step – a chance to load the body up for what it was meant to do. It essentially allows the athlete to reposition the body (or center of mass) more efficiently to load and explode. Ever wonder why sprinters use a starting block?

Look at all like an athlete’s body position once they step back and begin to move forward?

This topic has been covered in previous point/counterpoint articles in the NSCA journals and debated on forums, blogs and seminars alike. For me, I have been encouraging the “false step” or “plyo step” the past few years because it is ‘normal’ for athletes to move that way. As a matter of fact, one of the first things I do is put them in an athletic parallel stance position and ask them to accelerate for 10 yards. Not once have I seen them not step back provided I do not cue them to do so.

Keep in mind that previous research done (Kraan, GA, van Veen, J, Snijders, CJ, and Storm, J. Starting from standing: Why step backwards? J Biomech 34: 211–215, 2001.) indicates that stepping back is instinctive in up to 95% of subjects. Pretty telling, right? Even so, many coaches will still argue this technique slows the athletes down.

I think it is safe to say most would agree that deadlifts are great for building maximal lower body strength. Elite Olympic weightlifters are generally able to lift more loads in this lift compared to other free weight exercises. I know personally that I like to use it to develop lumbar extensor strength, as well as in place of the squat if I want to avoid spinal compression from the weight of the bar.

In the past I have heard some strength coaches say they don’t use a hex bar for deadlifts because it is not the same as lifting a straight bar. While not always sure exactly what they mean by that, I found a recent article in the July 2011 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research very insightful. The researchers looked at the difference between straight and hexagonal bar deadlifts in submax loading situations.

The concern with deadlifting has always been stress on the spine. The study notes:

“For world class athletes lifting extremely heavy loads, lumbar disk compression forces as large as 36,400 N have been reported.”

Lifters have long been encouraged to keep the barbell as close to them as possible to reduce the moment arm. The issue with the straight bar is that it can impinge on the body. Thus, the trap bar or hex bar apparatus was developed. The researchers hypothesized that the hex bar would reduce the joint movements and resistance moment arms. In addition, they hypothesized that larger forces would be produced with the submax loads.

The study use 19 male powerlifters and was conducted 3 months after their most recent competition where most were at the end of a training cycle aimed at matching or exceeding their previous competition performance. The subjects (following their own warm-up) performed HBD and SBD at 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 and 80% of his SBD 1RM. Twelve markers were placed on the body for biomechanical analysis.