Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

One of the most common PT clients I see is an injured runner. There can be a umber of different reasons or factors involved leading up to a running injury, but I wanted to focus on this idea of gait retraining that is taking place today. With the advent of Born to Run and minimalist footwear, people have begun to question and debate what the best way to run is.

Is this suited for everyone?

Let me just say right away that I do not believe there is a simple answer here. Human beings are all unique and have different genetic and biomechanical makeups. What this means in effect is that they have their own set of “issues” if you will that I classify into common categories such as:

- Static alignment problems (arch, knee, hip, etc)

- Static and dynamic balance deficits

- Inefficient gait mechanics

- Muscle imbalances

- Soft tissue tightness

- Recurring pain patterns

The list could go on and on, but you get the point. The idea of “re-teaching” someone how to run differently than their natural motor pattern dictates in not easy and is a decision that should be well thought out and based on sound decision making. We are pre-programmed at birth with certain native motor patterns and running is one of those patterns. Generally, your brain finds the most efficient way for you to run in your own body.

Now granted, some run much better than others. Perhaps we can say athleticism plays a role in this, but as we grow and reach skeletal maturity our body type, training experience, strength and environment are also major factors . With that said, I know that runners with recurrent and/or chronic pain are looking for a finite solution to their problem. They grow frustrated when they are unable to log all their miles or finish a race.

If traditional PT or relative rest fails to alleviate the pain, we must delve deeper and look more closely at their gait. I think video analysis is a great tool for doing this. We use Dartfish at my clinic, and this is very useful for breaking down gait mechanics and detecting things like heel versus forefoot striking, overpronation, asymmetry side-to-side, trunk inclination, etc. Once we find things on video we must also correlate these findings to our clinical screening to uncover a cause and effect relationship.

Well, Thanksgiving is upon us in 2011. I want to wish you and your family a wonderful holiday. In today’s post I will review a November 2011 article in the American Journal of Sports Medicine that looked at the effect of the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injuries in male soccer players.

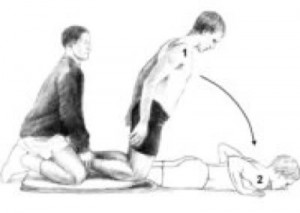

For those not familiar with Nordic hamstring exercises, see the photo below:

In this randomized trial, the researchers had 54 teams from the top 5 Danish soccer divisions participate. They ended up with 461 players in the intervention group (Nordic ex) and 481 players in the control group. The 10 week intervention program was implemented in the mid-season break between December and and March because this was “the only time of the year in which unaccustomed exercise does not conflict with the competitive season.

The trial was conducted between January 7, 2008 and December 12, 2008 with follow-up of the last injury until January 14, 2009. In the intervention group, all teams followed their normal training routine but also performed 27 sessions of the Nordic hamstring exercises in a 10 week program (as follows)

- Week 1 – 2 x 5

- Week 2 – 2 x 6

- Week 3 – 3 x 6-8

- Week 4 – 3 x 8-10

- Weeks 5-10 – 3 sets, 12-10-8 reps

- Weeks 10 plus – 3 sets 12-10-8 reps

The athletes were asked to use their arms to buffer the fall, let the chest touch the ground and immediately get back to the starting position by pushing with their hands to minimize the concentric phase. The exercise was conducted during training sessions and supervised by the coach. The teams were allowed to choose when in training it was done, but they were advised not to do it prior to a proper warm-up program.

And the results…..

I work with many runners in our clinic. I often see restrictions in the soleus. While the running community is warming up to soft tissue mobilization, many runners are still resistant to embrace it routinely and engage in it more so only when they are hurt or lacking flexibility.

STM (soft tissue mobilization) should be part of every runner’s maintenance program. Why? Simply put, repetitive stress takes its toll on the body. Rolling or releasing the tissue increases blood flow, eliminates trigger points, and facilitates optimal soft tissue mobility and range of motion.

In the diagram below, you can see common trigger points in the soleus. The X represents the trigger point & the red shaded area is the referred pain caused by the trigger point.

In the case of the soleus, restricted dorsiflexion could lead to other biomechanical compensations with running. Initially, this often creates a dysfunctional and non-painful (DN) pattern. Over time, this may eventually become a dysfunctional and painful (DP) pattern forcing runners to seek medical care. The terms DN and DP come from Gray Cook’s Selective Functional Movement Assessment (SFMA).

The gait cycle is certainly altered from dysfunction in this muscle. If ankle joint dorsiflexion is compromised (a common effect of soleus restrictions), there can be increased strain on the quads and altered movement in the hip. Overpronation and excessive hip adduction and internal rotation are common compensations seen with running. Other signs and pathology that may be associated with a soleus trigger point may include:

- Plantar fasciitis

- Heel pain

- Shin pain

- Knee or hip pain

- Back pain

As such, restoring mobility is important. A recent study revealed that immediate improvement in ankle motion can be attained with just a single treatment (click here for the abstract).

So how do you effectively resolve soft tissue issues in this area? I suggest using a foam roller or better yet the footballer and baller block in the Ultimate 6 Kit for Runners by Trigger Point (see pic below)

In my practice, I take care of many athletes ranging in age from 10 and up. Many of the injuries I see are related to over training and overuse. Common things I see in the clinic on a daily basis include but are not limited to:

- Tendonitis

- Shin splints

- IT Band Syndrome

- Patellofemoral pain

- AC joint pain/arthritis

The list can go on and on. There are many factors (inherent and training related) that contribute to such problems. I personally believe many problems can be prevented with better education, smarter training, coaching predicated on individuality and physical response, and of course adding in more recovery. Cross training is also a must – just look at what sport specialization at an early age has done to current injury rates.

You need not look any further than the declining age of patients walking through the door with what I term “repetitive microtrauma” injuries. I saw a 14 year old cross country female runner a few weeks ago who had her second stress reaction injury inside of 12 months. In addition, the rise in the number of Tommy John surgeries performed in the past decade with respect to those having them at an earlier age may serve as a harsh warning sign about doing too much too soon or doing too much of the same thing year round.

I say all this simply to say we must not be oblivious to the rise in these types of mechanical injuries. Throwing, swimming, and running are all activities that become dangerous if done in excess, and they also produce predictable injury patterns. So, if you are curious about some risk factors and how to better balance your training and manage these types of injuries, then check out a webinar I just did for Raleigh Orthopaedic Clinic last week (click on the screen shot below to view the webinar)

This presentation is ideal for athletes, parents, weekend warriors and sports coaches looking for practical, straightforward information on this topic with some foundational guidelines that can be applied objectively and immediately to injury management and recovery. If this information helps just one person avoid an injury or accelerate their recovery then I will be thrilled! Please feel free to forward this post to friends, share it on FB or tweet it!

I just finished presenting at our our second ACL Symposium of the year at the Athletic Performance Center last Saturday. Rehabbing and training female athletes has been a passion of mine for some time. Over the years, I have also developed a love for research and reading it, particularly studies on the ACL.

In my practice, I have incorporated jump landing, single leg training and deceleration based training for some time. While we all know females are 3-8 times more likely to suffer an ACL injury than males, we have not isolated the exact reason why. Researchers have offered some clues such as: wider pelvis, narrow femoral notch, smaller ACL, ligament dominance, limb dominance, natural laxity (hormonal factors), wider Q angles, and faulty muscle firing patterns to name a few.

Many of the structural factors are beyond our control. So, as practitioners, we must focus on the training. Consider the following study just published in the August 2011 edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine that basically reveals females develop peak valgus moments during deceleration during a drop landing maneuver, whereas males develop peak valgus forces during acceleration on the way back up:

Drop Landing

This article adds more evidence that females recruit and fire their muscles very differently than males. More importantly, it reiterates that we as coaches, therapists and S & C professionals need to be working on deceleration mechanics. I believe this starts with simple soft two legged drills such as:

- Small squat jump and holds

- Box drops and holds

- Forward line jump, stick and hold

- Lateral line jump, stick and hold

- 90 degree jump turn, stick and hold

In addition, one of my favorite drills is a single leg forward leap (hop) and stick working on deceleration. The athlete stands on the right leg and then pushes off forward landing on the left leg. Coaching the athlete to land softly on a bent hip and knee while avoiding valgus is important. I usually perform 2-3 sets of 5 reps on each side. Cueing with a mirror, auditory corrections and tactile cues are useful in encouraging proper form.

SL Stick (start)

SL Stick (finish)

It is important to keep in mind that the majority of non-contact ACL tears occur between 0 and 30 degrees of knee flexion. They also typically involve deceleration (landing, jump stop or change of direction), planting or cutting. For this reason, deceleration training must also involve programming for agility and change of direction.

On Saturday, I led the break-out session on deceleration training and covered a few key exercises I use with my athletes. These drills are layered on one another and the basic ones I begin with are:

- Stops – I have athletes accelerate out and then decelerate to a controlled two legged stop after 10-20 yards. Keep in mind allowing for a longer run will allow the athlete to gradually slow down, while decreasing the distance increases intensity and force on the knees. I coach breaking down with small “pitter patter” steps versus a sudden hard stop.

- 2 cone lateral shuffle stops – the athlete shuffles over 5-6 yards and then stops with good hip, knee and foot alignment working to keep the shoulders inside the knees (inside the box). I progress to multiple cone shuffles to increase intensity and maximize repetitive deceleration.

- Pro-agility drills – 3 cones are placed 5 yards apart and I combine linear and lateral movements between the cones layering #1 and #2 above in a continuous pattern to work on acceleration/deceleration combos and change of direction

- Y drill (4 cones) – the athlete runs forward to a cone 5-15 yards out and then performs a 45 degree cut left/right. The progression begins with directed and predictable movement and then advances to reactive cueing with auditory and visual cues.

- Arrow drill (4 cones) – The athlete runs 5-15 yards forward and then performs a 135 degree cut left/right and runs past the cone that serves as the bottom edge of the arrow head. This is much more demanding on the body (knee) and as such I only move to this after the Y drill has been mastered. In addition, I teach a hip turn (from Lee Taft) to reposition the hips and minimize torsion on the lower leg. I move from predictive to reactive agility as in the Y drill.

These exercises are a small sampling of my ACL prehab/rehab routine. I also include an enormous amount of single leg PRE’s and balance training as well. I believe the most important things we can currently do to reduce ACL risk in this population are:

- Screen our athletes to help identify risk (FMS, drop landing, dynamic strength,running/cutting analysis)

- Emphasize hamstring, gluteus medius and lateral rotator strengthening

- Teach landing mechanics and proper deceleration through neuromuscular exercise, biofeedback and repetitive cueing

- Refine proper cutting technique by teaching ideal angles and how to reposition the hips

- Empower coaches and athletes with simple yet effective body weight training routines that can be replicated on the field or court with the team

For now, the battle rages on. I hope you will join me in the quest to prevent these catastrophic injuries. I think as research evolves we will continue to see that the answer to promoting optimal stability at the knee will increasingly have more to do with addressing the hip and ankle. For now, we need to teach soft bent knee landing/cutting that shifts the body’s center of mass forward, while eliminating valgus loading as much as possible in the danger zone.