Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

It is that time of the year again. Everyone wants to lose weight and trim their waistlines. Abs, abs and more abs, right? I am all about some core training, but I am always concerned with some of the ab variations that I see commonly used at the gym and in group fitness environments.

Many exercise enthusiasts have tight hip flexors and poor abdominal control. Sprinkle in a history of low back pain or a prior disc injury along with straight leg abdominal exercises and now you have the perfect recipe for a possible back injury. Why is that? Well, the psoas originates from the lumbar spine and attaches to the lesser trochanter on the hip.

In the picture above, you can see how the muscle impacts the spine and hips. As you lower your legs toward the ground during an ab exercise, there is a reverse muscle action that takes place and resultant anterior shear force exerted on the lumbar spine. When the abdominal muscles cannot resist this motion, the lumbar spine hyperextends.

Many people will even report feeling a pop in the front of the hip while doing scissor kicks, leg lowering or throw downs. In many cases, this may be the tendon running/rubbing on the pectineal eminence. Unfortunately, long lever and/or ballistic abdominal exercises with inherently poor core stability/strength, fatigue and gravity working against you will create significant load and strain on the lumber spine. Ever wonder why you wanted to put your hands under your back while doing 6 inches? Your brain is trying to flatten the spine using your hands as it knows the hyperlordotic position is uncomfortable and threatening.

In light of this, I put together a little video for PFP Magazine revealing a safer way to work your abs and prevent undue stress and strain on your back. Check it out below.

Keep these modifications and progressions in mind the next time you hit the gym or a boot camp class focusing on core/ab training.

I work with many weekend warriors, strength training enthusiasts and overhead athletes in my practice. One of the more common dysfunctions I see in this population is either asymmetrical or general thoracic spine hypomobility (decreased range of motion).

This can predispose you to shoulder, back and hip dysfunction, as well as increase the risk for overuse injuries. In addition, it may also alter the natural biomechanics of movement, thereby negatively impacting performance. With all the sitting and screen time we engage in, it is no surprise we are developing a generation of people with forward heads, rounded shoulders and kyphotic posture.

This leads to reduced thoracic spine extension. Additionally, I often encounter decreased thoracic spine rotation. If this becomes restricted, asymmetrical overhead athletes may face increased stress on the lumbar spine, hips and glenohumeral joint. Common dysfunctions I treat related to this is rotator cuff tendinopathy, labral pathology, mechanical back pain, and hip pain to name a few.

To combat stiffness and promote more optimal mobility, I encourage my clients to perform daily mobility work. I have included a video I filmed for PFP Magazine in my column ‘Functionally Fit’ below that illustrates an effective way to combat reduced T-spine extension.

Be sure to check back for my next blog post on how to increase thoracic spine rotation.

I readily admit I have had an aversion to abdominal exercises that involve straight leg lowering since my days in pee wee football where we were forced to do lifts and holds a few inches above the ground. Some will relate to a modern day version of this exercise known as “six inches.”

As someone with tight hip flexors and who has personally suffered from sciatica in the past, I am NOT a fan of abdominal training that exposes the lumbar spine to large loads and undue risk related to exercises that involve long levers (e.g. throw downs, scissors, etc) and place high shear force on the spine.

I was reminded of why I feel this way in a fitness class this past week. I take a cycle/core class at my local gym and have done a traditional spinning class twice per week for 3 years. After 45 minutes of cycle, we move to a fitness room for core. I have done this new format for three weeks. This week we were asked to do a series of exercises which included “banana rolls.” If you are unfamiliar with this move, check out You Tube for some video demos.

While this exercise may be effective for core strengthening, I can honestly say as one who has never done the move before that trying to execute it as part of a continuous sequence of movements without rest between the moves was very hard to do with proper form. The fatigued state encouraged using momentum and straining to simply get the movement done (not to mention the fact my greater trochanter was sore from the rolling on the hard aerobic floor).

The next day I woke up with low back pain. My back has not hurt like that in years. In light of the role the iliopsoas plays by virtue of its attachment on the lumbar spine, we must consider the impact of reverse muscle action and how it creates shear on the lumbar spine during movements that rely on stabilization with the legs extended against gravity. Additionally, for those clients like me with muscle tightness, increased lumbar lordosis and a history of low back disorders, health and fitness professionals must consistently evaluate safety and efficacy as well as trying to challenge clientele in a workout session.

For all of these reasons, I increasingly rely on neutral spine anti-extension and anti-rotation training exercises in my programming for athletes and clients of all ages and abilities. That is not to say I never do rotational or active movements. They are appropriate given the right order, progression and demands of the respective individual. I just think we must consider form and risk versus reward in exercise programming.

The exercise video below illustrates how to use sliders in a tall plank position to accomplish great core activation and hip/shoulder stability without stressing the lumbar spine with long lever movements. Keep in mind that quality should override quantity in terms of deciding repetition schemes. Do not let the desire to fatigue clients cause form to suffer as this may increase injury risk.

For more specifics on the execution and progression/regression of this particular exercise, click the link below to read my most recent exercise column for PFP Magazine.

Suffice it to say I will not be doing banana rolls again. While I am not completely discarding the exercise, I do think it should be done in a non-fatigued state and taught incrementally if done at all. Most importantly, we as fitness professionals must always remember to program exercises based on fatigue and skill level, while carefully weighing risk versus reward in group or individual sessions.

There seems to be consistent questions, debate and studies done with respect to stretching. As the thought of more closely analyzing the quality of movement (FMS, Y-Balance testing, SFMA for example) moves to the forefront in the PT and fitness world, many search for the right mix of exercise to maximize mobility.

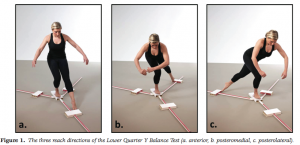

I count myself as a supporter and follower of the work of Gray Cook and Stuart McGill. While I may not agree 100% with all of their ideas, I generally consider them to be brilliant minds and ahead of the curve. I have been using the FMS in my practice for some time now and have also begun to incorporate Y-Balance testing as well (see pic below courtesy of the IJSPT)

The Y-Balance test may not have significant relevance to hip mobility as much as it does limb symmetry, but I included it here to illustrate my point in observing kinetic chain movement to help determine where the weak link or faulty movement pattern may be. It gives us valuable information with respect to strength, balance and mobility.

With the revelation that FAI is more prevalent than we knew (click here for my post on FAI), I am always interested in hip mobility and how to increase movement in the hip joint. Limitations in hip mobility can spell serious trouble for the lumbosacral region as well as the knee.

I currently use foam rolling, manual techniques, dynamic warm-up maneuvers, bodyweight single leg and hip/core disassociation exercises and static stretching to increase hip mobility. However, I am often faced with the question of what works best? Is less more? How can I make the greatest change without adding extra work and unnecessary steps?

Well, Stuart McGill and Janice Moreside just published a study in the May 2012 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research that sought to examine three different interventions and how they improve hip joint range of motion. Previous work has been focused on the hip joint alone, and they wanted to see how other interventions impacted the mobility of the hip. Click here for the abstract

Most adult males are in search of that ever elusive six pack, right? Well, most intelligent trainers and strength coaches are well aware that there is so much more than just crunches to making the core functional.

With that said, I believe abs may be one of the most over trained sets of muscles today. Some people are doing ab work daily. Why? Our abs function daily to stabilize and resist force, as well as activate trunk movements.

In reality, the aesthetics of the midsection have far more to do with nutrition and body fat than the number of crunches one does. My aim today is not to discuss this, but instead to talk about an interesting article in the latest Strength and Conditioning Journal that discusses the effects of over training the rectus abdominis on weightlifting performance.

In this article, Ellyn Robinson discusses the best way to allow athletes to stabilize weight overhead during complex lifts such as snatches, cleans and jerks. She aptly points out that if an athlete cannot stabilize the weight overhead, he/she could miss the lift in front or behind the body.