Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Dysfunctional movement is common with shoulder pain and impingement. One dysfunction you may encounter is a downwardly rotated scapula. If upward rotation is limited, a client will display excessive shoulder flexion above 90 degrees when the humerus is in maximal internal rotation. Typically, a person will have minimal flexion beyond 90 degrees if the scapula is moving properly.

Upward rotation of the scapula is the result of a force couple between the upper and lower trap along with the serratus anterior. If any of these muscles are weak, rotation can be limited and overpowered by the rhomboids and levator scapulae muscles (both downward rotators). This pattern of muscle dominance is common.

Additionally, tightness in the rhomboids, levator scapulae, pec minor or latissimus can also restrict normal mobility. It is probably safe to assume stretching of the chest and lats would be helpful, but it is critical to encourage the proper muscle firing patterns in the traps and serratus anterior as well.

Below is a video demonstrating wall slide shrugs. The shrug should be done at or above 90 degrees. You can perform reps at multiple angles or move to end range and perform a series there.

Application: The exercise is designed to encourage upward rotation in a more functional manner as opposed to traditional shrugs with the arms at the side. While I am not opposed to traditional shrugs with little or no weight for basic elevation, this position generally tends to activate the rhomboids and levator scapulae which is not desired given their natural dominance pattern.

The wall slide shrugs should not create any pain or discomfort. However, they may feel awkward particularly if the client has a faulty muscle activation pattern. As muscle tightness resolves and strength improves, clients should gain more mobility and optimal shoulder function.

By far the most common problem I see in the clinic is shoulder pain. Most of the time it is related to overuse, rotator cuff tendonitis/impingement and labral tears. Because we are geared more toward sports rehab, I also treat a lot of overhead athletes (baseball players, volleyball players and swimmers).

A common thing I will see in those suffering from impingement or rotator cuff pain is scapular winging. Most of the time the muscle is simply deficient in strength/endurance and it along with the lower trap become overpowered by the upper trap, levator or even the rhomboids. Shortened scapulohumeral muscles, poor posture and pec tightness can also impact winging.

There are many traditional exercises such as serratus punches, push-ups with a plus, and serratus plank push-ups to name a few, but I wanted to include a closed chain exercise that can be very effective for facilitating proper activation of the serratus – quadruped rocking.

In the video, I show it with both hands fixed on the floor progressing to one hand (on the involved side). The key is quality of movement throughout. After you check out the video, be sure to scroll down and click the link to a full column I wrote for PFP magazine on this exercise as it further explains the technique and application.

Click here to read the online column for PFP Magazine.

Shoulder impingement and scapular dysfunction are common issues that plague many clients. Research indicates that certain muscles tend to dominate others while other muscles fatigue easily leading to faulty movement patterns and increasing the risk for impingement. Muscle length and posture are also key factors to consider.

I like to use a mini-band retraction with clients exhibiting excessive scapular abduction. In the video below, you will see a simple, yet effective exercise to address this faulty alignment of the scapula. Keep in mind, you must observe the client or patient from behind with the scapula exposed to properly assess alignment and movement.

This exercise is designed to strengthen the middle trapezius and rhomboids. In addition, it will improve scapular stability. Scapular abduction is usually more evident with elevation from 90-180 degrees as the ratio of scapular movement to glenohumeral movement is 1:1 instead of the normal 1:2 ratio throughout since the scapula is already in an excessively abducted posture at rest.

To read more on the application and exact execution of this exercise, click here to read my column for PFP Magazine.

Rotator cuff tears are common injuries, especially among active middle age men. As researchers and scientists seek for better ways to promote healing and more optimal surgical outcomes, PRP continues to get lots of attention. If you want a basic primer on PRP, click here to read one of my earlier posts on it.

In a recent study in the October 2011 American Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers looked at the effects of PRP on patients undergoing surgery for full thickness rotator cuff tears. This is the first prospective cohort-control study to investigate the effect of PRP gel augmentation during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Forty two patients were included in the study (average age of 60), with 19 undergoing arthroscopic repair with PRP and 23 without.

Outcomes were assessed preoperatively and at 3, 6, 12, and finally at a minimum of 16 months after surgery (at an average of 19.7 +/- 1.9 months) with respect to pain, range of motion, strength, and overall satisfaction, and with respect to functional scores as determined using multiple assessment tools. At a minimum of 9 months after surgery, repaired tendon structural integrities were assessed by magnetic resonance imaging.

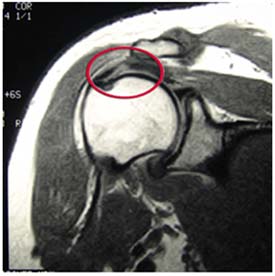

Below are images defining a full thickness rotator cuff tear:

Partial (left) vs. Full (right)

Full Thickness Tear on MRI

This post is a follow-up post to one of my previous ones, A Closer Look at Push-ups & Modified Push-ups, based on some dialogue with a reader. Click the link to familiarize yourself with the background. Some people simply do not agree with my assertion that modifying and or limiting end range of motion with certain exercises such as bench press, push-ups and flies is needed to preserve shoulder health long term.

So many people want to hitch their wagon to “simply strengthen the scapula” as a fix all solution. While I agree 100% that scapular stabilizer and cuff strengthening goes a long way, we would be foolish to ignore joint biomechanics, physics and kinesiology when examining how loads affect joint structure and function over time.

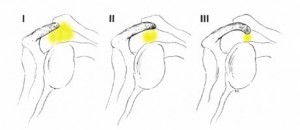

I will start out by saying I ascribe to the idea that a healthy joint should be able to move through full range of motion. My question to you is with how much load and how many times over and over again before destructive microtrauma sets in. With that said, how many healthy shoulder joints do you think are working out in gyms across the world today? Without an x-ray, it is impossible to know if you have a type I (normal), II (flat) or III (hook-shaped) acromion. Your genetics do make a difference in your risk for developing shoulder problems, as types II and III are more prone to impingement (see photos below)

This is one risk factor that cannot be mitigated by prehab if you will. I would also challenge you to consider that loading the shoulder repetitively with heavy loads in the furthest depths of shoulder horizontal abduction (bar touching the chest in bench press or lowering DB’s well below the plane of the body with flies) will eventually create atraumatic shoulder pathology.

Ever wonder about things like:

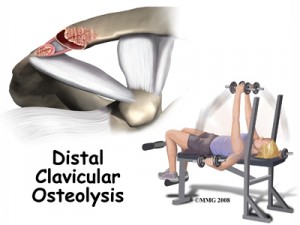

- Osteolysis of the distal clavicle

- Anterior shoulder laxity (over stretching the anterior capsule and joint structures over time)

- Creating impingement with repetitive motion in the presence of poor bony architecture, a thickened bursa or inadequate shoulder stability

While some may argue lifting does not create instability (it is known that bench press may lead to subtle posterior instability over time), I don’t think we can question the impact of weight lifting on clavicle destruction. Men more commonly develop acromio-clavicular arthritis, and osteolysis of the clavicle is common with lifting exercises such as bench press, dips and upright rows.

Click here for an article discussing osteolysis of the clavicle. The authors specifically mention modifying or avoiding certain weight lifting techniques base on pain and radiographic findings. I think we must as fitness professionals, strength coaches and educators look at the long term implications of lifting techniques on long term shoulder health and function.

Most would not hesitate to say they would do anything to avoid shoulder surgery if they knew their exercise habits might pose a risk for a future procedure to alleviate pain and restore function. I firmly believe avid recreational weight lifters and bodybuilders should modify range of motion with many of these pressing and lifting motions to be safe. This includes blocking full range bench press, modifying flies and push-ups, avoiding deep dips and generally minimizing how often they choose to do dips and upright rows. I also feel most people over age 35 or 40 should minimize the frequency of dips and upright rows as risk outweighs reward over time with repetitive loading of the clavicle (particularly if they have a long history of weight lifting already).

Take a look at the x-ray below showing osteolysis. You can often see a widening at the AC joint. Many times, these patients must undergo steroid injections, rest, activity modification and even a distal clavicle excision to resolve the pain.

Call me conservative or crazy, but I know personally how limiting bench press/fly range of motion eliminated my cuff pain in less than 2 weeks years ago when I was in college. Additionally, I currently have two patients in my clinic with shoulder injuries:

- A 19 y/o male hurt doing submax loads full range with a barbell

- A 60 plus y/o male who had arthroscopic repair of a torn supraspinatus that occurred while doing dumbbell flies (submax loads) on a flat bench lowering the dumbbells far below the parallel

Two patients decades apart hurt by the same mechanism – a biomechanical mismatch and repetitive microtrauma. So, my own body, years of clinical and training experience, and research studies have led me to conclude that modifications for those choosing to do resistance training 2-3 plus times per week for many years on end are necessary to have healthy shoulders for years to come. If you value your shoulder health and that of your clients, consider restricting depth, reducing shoulder abduction angels with pressing and carefully selecting and or limiting certain exercises based on client medical history and functional goals.