Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

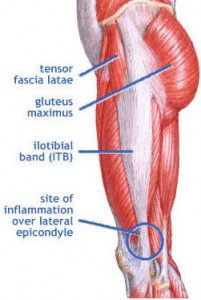

So, a very common issue I see in runners is iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome. In a nutshell, it involves excessive rubbing or friction of the ITB along the greater trochanter or lateral femoral epicondyle. It is more common along the lower leg just above the knee and typically worsens with increasing mileage or stairs.

The ITB is essential for stabilizing the knee during running. Several factors may contribute to increased risk for this problem:

- Muscle imbalances (weak gluteus medius and deep hip external rotators)

- Uneven leg length

- High and low arches

- Increased pronation leading to excessive tibial rotation = friction of the band

- Improper training progression

- Faulty footwear

- Poor running mechanics

- Limited ankle mobility (specifically dorsiflexion)

- Tightness in the tensor fascia latae (TFL) and glute max

Related information on this topic include a 2010 study published in JOSPT on competitive female runners with ITB syndrome:

Click here to see the abstract of the study

Click here to read an earlier blog post analysis of the above research article

Common signs and symptoms include stinging or nagging lateral knee pain that worsens with continued running. Hills and stairs may further aggravate symptoms. Some runners even note a “locking up” sensation that forces them to stop running altogether. How do I treat this?

This is a quick post to announce that I have joined forces with Allied Health Education, a new company founded to provide relevant education for allied health professionals, personal trainers and strength and conditioning professionals. It is a therapist owned company dedicated to delivering affordable evidence-based continuing education.

I will be doing webinars on SLAP tears (this one is open for registration now) and FAI as well as a live one day course in September on the knee (breakouts will focus on running, ACL and arthritis). For more information and current course listings, visit them online at www.alliedhealthed.com.

So, I treat a number of fitness enthusiasts in the clinic and many include Crossfit clients. Recently, I evaluated a 38 y/o male on 2/16/12 with a 3 month history of right shoulder pain. He performs Crossfit workouts 6 days per week. His initial intake revealed:

- Constant shoulder pain that worsens with overhead movements

- Pain with bar hangs, overhead squats and wide grip snatches

- Unable to do kipping (only doing strict form pull-ups)

- Pain if laying on his right side at night

- No c/o neck pain, referred pain or numbness/tingling

Notice the shoulder position during the kipping pull-up and overhead squat below. This is a position of heightened risk for the shoulder.

His exam revealed the following:

- Normal range of motion

- Strength within normal limits except for supraspinatus and external rotation graded 3+/5 with pain

- Positive impingement signs

- Negative shrug sign

- Negative Speed’s and O’Brien’s test

- Tender along distal supraspinatus tendon

Based on the clinical exam, it was apparent he had rotator cuff inflammation and perhaps even a tear. Keep in mind he had not seen a physician yet. I began treatment focused on scapular stabilization and rotator cuff strengthening as well as pec and posterior capsule stretching to address the impingement. Ultrasound and cryotherapy were used initially to reduce pain and inflammation.

One month following the eval

By 3/14/12, his pain was resolved with daily activity and he had returned to snatches and push-press exercises without pain. He still could not do overhead squats with the Olympic bar pain free, but he could with a pvc pipe. Strength was now 4/5 for supraspinatus and 4+/5 for external rotation. All impingement tests were now negative as were Speed’s and O’Brien’s testing.

One of the most common issues I see in the clinic with active exercise enthusiasts between the age of 20 and 55 is shoulder pain. Weightlifting has been popular for ages, but Crossfit is all the rage these days. Both disciplines involve overhead lifts. The key thing to remember when performing overhead repetitive lifts is how load and stress not only affects strength and power, but how it impacts the joint itself.

Pull-ups and pull-downs are staples for most clients I see. As a therapist and strength coach, I am always thinking and analyzing how variables such as grip, grip width, arm position, scapular activation, trunk angles etc influence exercise and how force is absorbed by the body. One such exercise I have spent time studying and tweaking is the lat pull-down.

Consider for a moment how width and grip impacts the relative abduction and horizontal external rotation in the shoulder at the top and bottom of the movement in the pictures below (start and finish positions are vertically oriented):

It should be common knowledge for most, but I will state it for the record anyway – you should NEVER do behind the neck pull-downs. Beyond the horrible neck position, this places the shoulder in a dangerous position for impingement and excessively stresses the anterior shoulder capsule. A wider grip (be it with pull-ups, pull downs, push-ups) will always transfer more stress to the shoulder joint because you have a longer lever and greater abduction and horizontal external rotation.

So, what bearing does this have in relation to the rotator cuff and SLAP injuries? For more information and details on the application of the grip choice, click here to read the full column I did for PFP Magazine this month. Stay tuned for my next post (a follow-up to this one) one of my Crossfit patients who now only has pain with overhead squats and how my differential diagnosis and rehab has led me to conclude what is wrong with his shoulder. Keep in mind we must learn to train smarter so we can train harder and longer without pain and injury. Biomechanics and understanding your own body really does matter.

Kettlebells are very popular training tools these days. I find them useful in many ways – improving grip strength, core activation, asymmetrical loading, etc. With that said, I also feel with movement flaws and/or improper technique, they carry an inherent injury risk.

It is interesting to note that some people find swings to be very therapeutic and good for their back, while others who are capable of lifting very high loads with traditional lifts find them to be irritating to the spine. So why is this?

If you are like me, knowing the “why” or “cause and effect” behind exercise is very important. I am not one to blindly use an exercise without knowing its intended purpose and then quantifying risk vs. reward and results. So, it was with great interest I read Stuart McGill and Leigh Marshall’s recent article on kettlebell swings, snatches and bottoms-up carries in the NSCA Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research (Jan 2012).

While the sample size is small, I think the article provides some gems in regard to training given no one has really looked at spine loading during various swings and carries. The authors used surface EMG to record muscle activation of the back, hip and core muscles throughout the various exercises – swing, swing with Kime (abdominal pulse at top of the swing), swing to snatch, racked carry and bottoms-up carry.

Without going into all the tiny details, I wanted to share what I consider to be some key takeaways for rehab and training:

- Unlike traditional low back extension exercises such as lifting a bar or squatting exercises, the swing creates a relatively high posterior shear force (namely L4 on L5) in relation to the compressive load – this may explain why some powerlifters have no issues with heavy dead lifts but are bothered by swings

- Both compressive and shear forces were highest at the beginning of the swing

- From a compressive standpoint loads with a 16 kg kettlebell (swing) are less than one-half of that of lifting 27 kg on an Olympic bar and these would seemingly pose a low relative injury risk

- KB swings do appear to require sufficient spine stability in this shear mode to ensure that is is a “safe” exercise selection

- Those with back pain develop movement flaws and the authors report one of the most common is to move the spine under load instead of the hips – so instead of hip hinging, injured clientele are more apt to shift or bend the spine leading to repetitive and harmful forces

- A modified approach to swings with careful cueing and progression is suggested for clinicians

- The bottoms-up carry poses more challenge to the core musculature likely due to requiring more grip strength (thus stiffening the core per McGill in Ultimate Back Fitness & Performance) as well as necessitating more control to carry it, hence making it a good choice for training in terms of activation of these muscles

So, in my mind kettlebell training (like any other form of training) requires proper form, movement assessment and an intimate knowledge of the client’s medical and training history. In addition to that, we must carefully scrutinize execution of the exercise and deliver appropriate feedback and analysis.

While maximal shear occurs at the bottom, I cannot help but wonder about the potential impact of tight iliopsoas muscles given their unique relationship to the lumbar spine and reverse muscle action. It would be interesting to know if those with a greater anterior tilt and tightness are more likely to experience higher shear forces or potential back soreness over time.

This brings the discussion back to quality of movement and movement assessment. In my mind, adequately assessing the hips (flexibility, strength and stability) is also a key variable in determining how best to approach integrating the swings. As Gray would say, the lumbar spine needs stability while the hips require mobility.

A lack of hip mobility is definitely a relative precaution for swings in my mind. On top of that, fundamental hip strength/stability and core strength should be evident. Perhaps even regressing to rudimentary hip thrusts and bridges may be the best place to start for those needing a primer on form and proper movement before moving to a basic swing.

Nonetheless, a big thanks to Stuart McGill and Leigh Marshall for this work and giving us some practical food for thought. I hope this information helps you as much as it did me. May your training be safe and effective!