Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

It is time to clear out some product inventory this year. To that end, I am offering a 50% off sale for one week only. This sale is on all physical products as well as e-books. I am also offering this discount on my printed version of the Ultimate Rotator Cuff Training Guide, of which I only have five remaining copies.

Simply enter code BFIT50 at checkout to save 50% on your entire order. Click Here to view all products.

This sale will end Monday July 18, so act now while supplies last.

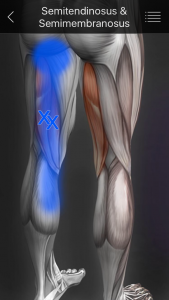

Many people suffer from chronic hamstring pain. The question is what is the root source the pain? As a seasoned clinician, I see many patients who present with pain in the upper hamstring/ischial region. Referral sources can include the low back, hip, SI joint, proximal hamstrings, gluteals, piriformis, and ischial bursitis to name a few. In some cases, the pain can be multi-factorial as I see some runners with low level discogenic (nerve) pain and proximal hamstring tendinopathy. The sciatic nerve and its proximity with the hamstrings necessitates thoroughly vetting the symptoms and its pattern in each client. Assessing SLR, slump test, reflexes, myotomes and dermatomes is a must.

Determining what the exact source of can be difficult and requires a good subjective exam and objective testing. For the purposes of this particular post, I am focusing on the proximal hamstrings themselves as the primary source of the pain, as I see so many who struggle with proximal tendinopathy who have seen many providers with little relief.

I treat many runners and middle aged adults who experience this high hamstring or buttock pain that is often worse with:

- Sitting

- Forward bending

- Walking or running uphill

As with traditional hamstring strains, eccentric strengthening is a must for this population. However, we must consider the myofascial component and contributions to this pain as well. In many cases, these patients have ischial tuberosity tenderness. Consider the referral pattern of the medial HS illustrated below:

I typically like to consider using hip and core strengthening, dry needling, IASTM, stretching and eccentric strengthening to address the pain. If I feel the problem may include a sciatic nerve component and there is an extension bias, I will utilize some PA glides and extension exercises too. In addressing this pain pattern, we must be thorough.

A 2014 case study published in JOSPT looked at a case study with two runners (71 and 69 y/o men) who were treated with eccentric exercises, trigger point dry needling and lumbopelvic stability exercises. The rehab was phase based and the results are as follows:

Patient 1 was treated in physical therapy for 9 visits over 8 weeks. At discharge, he had achieved his goal of running 8 to 10 km 5 times each week pain free. An e-mail received 6 months following discharge noted that he had remained symptom free with all activity and that he completed a triathlon symptom free.

Patient 2 was seen in physical therapy for 8 visits over the course of 10 weeks and discharge were performed by the same therapist who performed the initial evaluations and oversaw each treatment. He was discharged after running 30 km without symptoms and reporting significant decrease in hamstring pain. The patient was seen 6 months later in physical therapy for unrelated right shoulder subacromial impingement but reported no hamstring symptoms and that he had participated pain free in a marathon.

In my practice, I have found dry needling, heat and soft tissue work to be very helpful along with stretching and strengthening. I like to use eccentric PREs and hip stability work to resolve proximal hamstring pain. Specifically, I have used the following two exercises with very good results:

Single leg RDL

Supine reverse hamstring curls using gliding discs

Both of these exercises are effective in promoting eccentric hamstring strength, hip stability, and improved hamstring mobility. Furthermore, they can be effectively used in rehab, rehab and training situations. I routinely use them in all of the above. For a more detailed explanation of the reverse curls, be sure to check out my upcoming Functionally Fit column at www.fit-pro.com.

Keep in mind that hamstring pain can be caused by one or multiple sources. It is best to seek a medical evaluation to determine the exact source of pain and address it safely and effectively. Exercises such as the ones demonstrated in this post represent a few options for addressing hamstring strains/tendinopathy. Others may include Nordic hamstring curls, prone eccentric hamstring curls and hamstring walkouts. Using manual interventions along with exercise is often effective in accelerating and optimizing full recovery.

Reference

Jayaseelan DJ, Moats N, Ricardo C. Rehabilitation of Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy Utilizing Eccentric Training, Lumbopelvic Stabilization, and Trigger Point Dry Needling: 2 Case Reports. J Orhtop Sports Phys Ther 2014 (44)3:198-205.

As a sports medicine professional and physical therapist working with lots of athletes after ACL surgery, I am always looking for ways to improve post-op rehab and prevent a subsequent ACL injury. While we have lots of research looking at neuromuscular, genetic, sex and morphologic risk factors, we have not been able to make significant progress in injury reduction. So many athletes suffer the dreaded “pop” making a simple athletic maneuver they have done a thousand times before.

Based on nearly 19 years of experience training and rehabbing athletes from youth to professionals, I see strong links to a genetic predisposition (family history and prior injury) as well as concerns over neural fatigue. We already know the age of injury is a significant as research indicates those tearing at a younger age (around 20-21 y/o) are more likely to suffer a second injury. But what we know less about is the impact of ankle biomechanics (namely limited dorsiflexion) and how proximal weakness in the hip affects injury risk.

The latter topic was the focus of a study just published in the current edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine. In this prospective study, researchers sought to determine if baseline hip strength can predict future non-contact ACL tears in athletes.

Why is it that athletes performing a movement they have done so many times suddenly tear their ACL? We have been studying ACL injury and prevention for many years now, and despite our best efforts, we have not made marked progress in preventing the number of ACL injuries. In addition to anatomical variants and perhaps some genetic predisposition, I feel that the earlier push for sports specialization in our society resulting in increased training/competition hours is a major factor.

The term ACL fatigue may or may not be familiar to you. But in essence, this theory would suggest that after a certain number of impacts/loading, the ACL becomes weakened and less resistant to strain. You could almost compare this to a pitcher who suffers an injury to his medial collateral ligament with too much throwing.

As someone who is consistently rehabbing athletes with ACL tears and screening athletes to assess injury risk, I am always interested in how we can keep people from suffering such a devastating non-contact injury. A recent article in the American Journal of Sports Medicine sought so assess ACL fatigue failure in relation to limited hip internal rotation with repeated pivot landings.

We already know that hip mobility is often an issue for our athletes. Researchers at the University of Michigan sought to determine the effect of limited range of femoral internal rotation, sex, femoral-ACL attachment angle, and tibial eminence volume on in vitro ACL fatigue life during repetitive simulated single leg pivot landings.

I work with lots of runners, both recreational and competitive, who are seeking to improve performance or overcome injuries. The most common issues I see are iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) and patellofemoral knee pain (PFP). With every runner, I routinely perform FMS and video analysis to get a better understanding of their movement patterns, gait mechanics and asymmetries.

Without question, they tend to ask me if there is a better way to run. Obviously, every accomplished runner has his/her own opinion on the matter. Some prefer forefoot or midfoot strike, while other do just fine with a heel strike pattern. In essence, we do not have any sound research or biomechanical evidence to declare one a winner. Since I work with many injured runners, I am always seeking to find the most efficient ways to reduce injury risk and eliminate pain.

A paper just published in the September 2015 American Journal of Sports Medicine by Boyer and Derrick sought to answer the question of how shortening the stride length or altering foot strike pattern may impact certain variables. Specifically, the authors sought to compare step width, free moment, ITB strain and strain rate, and select lower extremity frontal and transverse plane kinematics when stride length was shortened 5% and 10% in habitual rearfoot and habitual mid-/forefoot runners using both strike patterns while shod.