Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Many of my clients need to improve shoulder and pillar stability. Combating poor glenohumeral and scapular stability and insufficient trunk stability is a must to reduce injury risk, resolve shoulder and back pain and eliminate compensatory motion with exercise, sport and life.

The following two exercises are “go to” ones I utilize to do just this.

The links above are for two recent exercise columns I authored for PFP Magazine. These exercises include load bearing using the client’s bodyweight and include progressions and regressions.

Improving lateral chain strength is always a priority when training or rehabbing athletes. Improving anti-rotation stability is particularly important for injury prevention and dissipation of forces in the transverse plane. Whether working with a post-op ACL client or training an overhead athlete, I am always seeking ways to increase torso/pillar stability to increase efficiency of movement and reduce injury risk.

This video below from my Functionally Fit series for PFP Magazine will demonstrate a great exercise do accomplish these training goals.

Emphasis should always be placed on maintaining alignment. Do not progress the load too quickly, and be cautious if using the fully extended down arm position if clients have a history of shoulder instability or active shoulder pathology as this places more stress on the glenohumeral joint. Below are some progressions and regressions as well:

Regressions

1. Decrease the hold time as needed to maintain form and alignment

2. Allow the kettlebell to rest against the right dorsal wrist/forearm

3. Stack the top foot in front of the other foot as opposed to stacking them on top of one another to increase stability

4. Bend the knees to 90 degrees to reduce the body’s lever arm

Progressions

1. Increase the weight of the kettlebell and/or increase hold time

2. Lift the top leg away from the down leg

3. Add light perturbations to the top arm during the exercise to disrupt balance and challenge stability

4. Perform the exercise with the down arm fully extended

Many people suffer from chronic hamstring pain. The question is what is the root source the pain? As a seasoned clinician, I see many patients who present with pain in the upper hamstring/ischial region. Referral sources can include the low back, hip, SI joint, proximal hamstrings, gluteals, piriformis, and ischial bursitis to name a few. In some cases, the pain can be multi-factorial as I see some runners with low level discogenic (nerve) pain and proximal hamstring tendinopathy. The sciatic nerve and its proximity with the hamstrings necessitates thoroughly vetting the symptoms and its pattern in each client. Assessing SLR, slump test, reflexes, myotomes and dermatomes is a must.

Determining what the exact source of can be difficult and requires a good subjective exam and objective testing. For the purposes of this particular post, I am focusing on the proximal hamstrings themselves as the primary source of the pain, as I see so many who struggle with proximal tendinopathy who have seen many providers with little relief.

I treat many runners and middle aged adults who experience this high hamstring or buttock pain that is often worse with:

- Sitting

- Forward bending

- Walking or running uphill

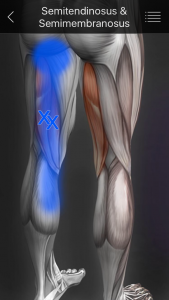

As with traditional hamstring strains, eccentric strengthening is a must for this population. However, we must consider the myofascial component and contributions to this pain as well. In many cases, these patients have ischial tuberosity tenderness. Consider the referral pattern of the medial HS illustrated below:

I typically like to consider using hip and core strengthening, dry needling, IASTM, stretching and eccentric strengthening to address the pain. If I feel the problem may include a sciatic nerve component and there is an extension bias, I will utilize some PA glides and extension exercises too. In addressing this pain pattern, we must be thorough.

A 2014 case study published in JOSPT looked at a case study with two runners (71 and 69 y/o men) who were treated with eccentric exercises, trigger point dry needling and lumbopelvic stability exercises. The rehab was phase based and the results are as follows:

Patient 1 was treated in physical therapy for 9 visits over 8 weeks. At discharge, he had achieved his goal of running 8 to 10 km 5 times each week pain free. An e-mail received 6 months following discharge noted that he had remained symptom free with all activity and that he completed a triathlon symptom free.

Patient 2 was seen in physical therapy for 8 visits over the course of 10 weeks and discharge were performed by the same therapist who performed the initial evaluations and oversaw each treatment. He was discharged after running 30 km without symptoms and reporting significant decrease in hamstring pain. The patient was seen 6 months later in physical therapy for unrelated right shoulder subacromial impingement but reported no hamstring symptoms and that he had participated pain free in a marathon.

In my practice, I have found dry needling, heat and soft tissue work to be very helpful along with stretching and strengthening. I like to use eccentric PREs and hip stability work to resolve proximal hamstring pain. Specifically, I have used the following two exercises with very good results:

Single leg RDL

Supine reverse hamstring curls using gliding discs

Both of these exercises are effective in promoting eccentric hamstring strength, hip stability, and improved hamstring mobility. Furthermore, they can be effectively used in rehab, rehab and training situations. I routinely use them in all of the above. For a more detailed explanation of the reverse curls, be sure to check out my upcoming Functionally Fit column at www.fit-pro.com.

Keep in mind that hamstring pain can be caused by one or multiple sources. It is best to seek a medical evaluation to determine the exact source of pain and address it safely and effectively. Exercises such as the ones demonstrated in this post represent a few options for addressing hamstring strains/tendinopathy. Others may include Nordic hamstring curls, prone eccentric hamstring curls and hamstring walkouts. Using manual interventions along with exercise is often effective in accelerating and optimizing full recovery.

Reference

Jayaseelan DJ, Moats N, Ricardo C. Rehabilitation of Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy Utilizing Eccentric Training, Lumbopelvic Stabilization, and Trigger Point Dry Needling: 2 Case Reports. J Orhtop Sports Phys Ther 2014 (44)3:198-205.

As a sports medicine professional and physical therapist working with lots of athletes after ACL surgery, I am always looking for ways to improve post-op rehab and prevent a subsequent ACL injury. While we have lots of research looking at neuromuscular, genetic, sex and morphologic risk factors, we have not been able to make significant progress in injury reduction. So many athletes suffer the dreaded “pop” making a simple athletic maneuver they have done a thousand times before.

Based on nearly 19 years of experience training and rehabbing athletes from youth to professionals, I see strong links to a genetic predisposition (family history and prior injury) as well as concerns over neural fatigue. We already know the age of injury is a significant as research indicates those tearing at a younger age (around 20-21 y/o) are more likely to suffer a second injury. But what we know less about is the impact of ankle biomechanics (namely limited dorsiflexion) and how proximal weakness in the hip affects injury risk.

The latter topic was the focus of a study just published in the current edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine. In this prospective study, researchers sought to determine if baseline hip strength can predict future non-contact ACL tears in athletes.

Why is it that athletes performing a movement they have done so many times suddenly tear their ACL? We have been studying ACL injury and prevention for many years now, and despite our best efforts, we have not made marked progress in preventing the number of ACL injuries. In addition to anatomical variants and perhaps some genetic predisposition, I feel that the earlier push for sports specialization in our society resulting in increased training/competition hours is a major factor.

The term ACL fatigue may or may not be familiar to you. But in essence, this theory would suggest that after a certain number of impacts/loading, the ACL becomes weakened and less resistant to strain. You could almost compare this to a pitcher who suffers an injury to his medial collateral ligament with too much throwing.

As someone who is consistently rehabbing athletes with ACL tears and screening athletes to assess injury risk, I am always interested in how we can keep people from suffering such a devastating non-contact injury. A recent article in the American Journal of Sports Medicine sought so assess ACL fatigue failure in relation to limited hip internal rotation with repeated pivot landings.

We already know that hip mobility is often an issue for our athletes. Researchers at the University of Michigan sought to determine the effect of limited range of femoral internal rotation, sex, femoral-ACL attachment angle, and tibial eminence volume on in vitro ACL fatigue life during repetitive simulated single leg pivot landings.