Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

This post is a follow-up post to one of my previous ones, A Closer Look at Push-ups & Modified Push-ups, based on some dialogue with a reader. Click the link to familiarize yourself with the background. Some people simply do not agree with my assertion that modifying and or limiting end range of motion with certain exercises such as bench press, push-ups and flies is needed to preserve shoulder health long term.

So many people want to hitch their wagon to “simply strengthen the scapula” as a fix all solution. While I agree 100% that scapular stabilizer and cuff strengthening goes a long way, we would be foolish to ignore joint biomechanics, physics and kinesiology when examining how loads affect joint structure and function over time.

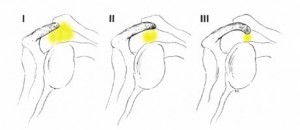

I will start out by saying I ascribe to the idea that a healthy joint should be able to move through full range of motion. My question to you is with how much load and how many times over and over again before destructive microtrauma sets in. With that said, how many healthy shoulder joints do you think are working out in gyms across the world today? Without an x-ray, it is impossible to know if you have a type I (normal), II (flat) or III (hook-shaped) acromion. Your genetics do make a difference in your risk for developing shoulder problems, as types II and III are more prone to impingement (see photos below)

This is one risk factor that cannot be mitigated by prehab if you will. I would also challenge you to consider that loading the shoulder repetitively with heavy loads in the furthest depths of shoulder horizontal abduction (bar touching the chest in bench press or lowering DB’s well below the plane of the body with flies) will eventually create atraumatic shoulder pathology.

Ever wonder about things like:

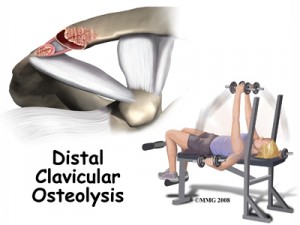

- Osteolysis of the distal clavicle

- Anterior shoulder laxity (over stretching the anterior capsule and joint structures over time)

- Creating impingement with repetitive motion in the presence of poor bony architecture, a thickened bursa or inadequate shoulder stability

While some may argue lifting does not create instability (it is known that bench press may lead to subtle posterior instability over time), I don’t think we can question the impact of weight lifting on clavicle destruction. Men more commonly develop acromio-clavicular arthritis, and osteolysis of the clavicle is common with lifting exercises such as bench press, dips and upright rows.

Click here for an article discussing osteolysis of the clavicle. The authors specifically mention modifying or avoiding certain weight lifting techniques base on pain and radiographic findings. I think we must as fitness professionals, strength coaches and educators look at the long term implications of lifting techniques on long term shoulder health and function.

Most would not hesitate to say they would do anything to avoid shoulder surgery if they knew their exercise habits might pose a risk for a future procedure to alleviate pain and restore function. I firmly believe avid recreational weight lifters and bodybuilders should modify range of motion with many of these pressing and lifting motions to be safe. This includes blocking full range bench press, modifying flies and push-ups, avoiding deep dips and generally minimizing how often they choose to do dips and upright rows. I also feel most people over age 35 or 40 should minimize the frequency of dips and upright rows as risk outweighs reward over time with repetitive loading of the clavicle (particularly if they have a long history of weight lifting already).

Take a look at the x-ray below showing osteolysis. You can often see a widening at the AC joint. Many times, these patients must undergo steroid injections, rest, activity modification and even a distal clavicle excision to resolve the pain.

Call me conservative or crazy, but I know personally how limiting bench press/fly range of motion eliminated my cuff pain in less than 2 weeks years ago when I was in college. Additionally, I currently have two patients in my clinic with shoulder injuries:

- A 19 y/o male hurt doing submax loads full range with a barbell

- A 60 plus y/o male who had arthroscopic repair of a torn supraspinatus that occurred while doing dumbbell flies (submax loads) on a flat bench lowering the dumbbells far below the parallel

Two patients decades apart hurt by the same mechanism – a biomechanical mismatch and repetitive microtrauma. So, my own body, years of clinical and training experience, and research studies have led me to conclude that modifications for those choosing to do resistance training 2-3 plus times per week for many years on end are necessary to have healthy shoulders for years to come. If you value your shoulder health and that of your clients, consider restricting depth, reducing shoulder abduction angels with pressing and carefully selecting and or limiting certain exercises based on client medical history and functional goals.

I think it is safe to say most would agree that deadlifts are great for building maximal lower body strength. Elite Olympic weightlifters are generally able to lift more loads in this lift compared to other free weight exercises. I know personally that I like to use it to develop lumbar extensor strength, as well as in place of the squat if I want to avoid spinal compression from the weight of the bar.

In the past I have heard some strength coaches say they don’t use a hex bar for deadlifts because it is not the same as lifting a straight bar. While not always sure exactly what they mean by that, I found a recent article in the July 2011 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research very insightful. The researchers looked at the difference between straight and hexagonal bar deadlifts in submax loading situations.

The concern with deadlifting has always been stress on the spine. The study notes:

“For world class athletes lifting extremely heavy loads, lumbar disk compression forces as large as 36,400 N have been reported.”

Lifters have long been encouraged to keep the barbell as close to them as possible to reduce the moment arm. The issue with the straight bar is that it can impinge on the body. Thus, the trap bar or hex bar apparatus was developed. The researchers hypothesized that the hex bar would reduce the joint movements and resistance moment arms. In addition, they hypothesized that larger forces would be produced with the submax loads.

The study use 19 male powerlifters and was conducted 3 months after their most recent competition where most were at the end of a training cycle aimed at matching or exceeding their previous competition performance. The subjects (following their own warm-up) performed HBD and SBD at 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 and 80% of his SBD 1RM. Twelve markers were placed on the body for biomechanical analysis.

Today I am going to share two pieces I have written for other publications as I think the exercises I discuss have real merit and broad application for competitive athletes and weekend warriors. I am a columnist for PFP Magazine and Endurance Magazine and these articles come from those publications.

Single Leg Theraband Activation Squats

The idea behind this exercise is applying progressive gradients of resistance that encourage the faulty motion (pulling the leg into adduction and internal rotation) to facilitate increased activation of the gluteus medius/minimus and small lateral rotators to create an anti-adduction/internal rotation force. Decreasing such moments at the knee will reduce IT Band issues, patellofemoral pain, ACL injury risk and overuse problems often seen in running.

Click here to see how to perform the exercise

Mobility Training for Endurance Athletes

It is no secret that endurance events require repetitive motion and often carry a higher risk of overuse injuries. In light of this, poor thoracic extension and/or limited ankle dorsiflexion negatively impact proper running and riding mechanics and lead to faulty movement patterns. Beyond physical stress, this reduces performance capacity as well. There are two simple mobility exercises to help correct imbalances that may be hindering you.

Click here (go to page 16) to see how to sustain your body with these exercises

I have been attending the 26th Annual Cincinnati Sports Medicine Advances on the Shoulder and Knee conference in Hilton Head, SC. This is my first time here and the course has not disappointed. I have always known that Dr. Frank Noyes is a very skilled surgeon and has a great group in Cincinnati as I am originally an Ohio guy too.

So, I thought I would just share a few little nuggets that I have taken away from the first three days of the course so far. I am not going into great depth, but suffice it to say these pearls shed some light on some controversial and difficult problems we see in sports medicine.

Shoulder Tidbits

- Fixing SLAP tears may not always fix shoulder pain as in many cases it may be in part due to posterior capsule tightness and anterior instability leading to internal impingement. Additionally, many of the docs here choose not to repair type 2 tears in those over 40 tears and provide a biceps tenotomy or tenodesis to instead to deliver more predictable pain relief as opposed to a labral repair.

- Intraoperative pain pumps in the shoulder are causing glenohumeral joint chondrolysis in the shoulder in many cases. According to the panel of docs, this has been seen in teenagers and patients in their twenties as well. They have often undergone other procedures from outside docs and then developed increasing pain afterward. Many have had to even undergo a total shoulder replacement after a few years post-op. The MDs here have suggested even post-operative Marcaine injections for pain relief in the shoulder should probably not be used. It was very sad to see an 18 y/o shoulder x-ray they put up that looked as if the patient was 80 years old.

- Double row rotator cuff tendon repairs seem to outperform single row repairs with respect to tendon healing (90% for DR and 76% for SR techniques in a comprehensive review of the literature)

- Stretching cross body horizontal adduction may be more important for throwers and overhead athletes than the sleeper stretch – best to have a therapist stabilize the scapula and then move the shoulder across the body keeping the shoulder in neutral rotation (it will tend to externally rotate)

- Arthroscopic stabilization is better than open surgery for posterior shoulder instability as the posterior cuff and deltoid are not violated, ROM recovery is more predictable, patient satisfaction is higher and there is a more predictable return to sport

Knee Tidbits

- Increased femoral anteversion and torsion is a developmental factor that does in fact control the knee to a great extent. The tibial tubercle-sulcus angle, thigh-foot angle and foot alignment is also key according to Dr. Lonnie Paulos. In cases of miserable patella mal-alignment, many will need de-rotation and re-alignment procedures to improve their symptoms.

- The consensus among the orthopods here was that using a bone-tendon-bone patella tendon autograft to reconstruct torn ACLs in the younger more active athletes (soccer players and football players) is preferable to a hamstring graft or allograft. Allografts did not seem to be the graft of choice by any of the docs for the younger patients. Some would use a hamstring autograft provided there was no MCL pathology. The PTG autograft was the gold standard for years (always my favorite graft choice for high level/demand athletes) so I was pleased to see the trend for this population moving away from the ST/gracilis HS grafts.

- Kevin Wilk, DPT (primary PT for Dr. James Andrews), was advocating restoring full and symmetrical ROM after ACL surgery. I tend to agree with this principle myself. However, Dr. Noyes was not in agreement and rather cautiously noted he would be okay with about 3 degrees of hyperextension on the repaired side no matter how much hyperextension was available on the other side. Kevin also noted that restoring full flexion was paramount to restoring running mechanics and speed in higher level athletes.

- The golden time to repair a MCL tear is in the first 7-10 days. Dr. Paulos also suggested it is absolutely necessary to fix the deep layer as well as the superficial layer. His talk emphasized how big of a mistake it is to not repair the deep layer. He also warns that the strength of the repair is less important than restoring proper length, tension and collagen.

- For PCL augmented repairs, a 2 bundle repair is repaired. Most of the docs like to use a quad tendon autograft from the contralateral thigh, but will take it from the same leg if patients insist. The consensus seemed to be that a repair should be done if there is 10 millimeters or more of drop off.

These are just some of the highlights I wanted to pass along. There was lots of other good stuff (much of it a nice review of anatomy, biomechanics and protocol guidelines for rehab) but I wanted to pass along some of these key items while they were fresh in my head. I will likely be sharing more in the future, particularly with respect to patello-femoral pain and SLAP tears as these are just so controversial in terms of surgical and rehab management.

The News and Observer (our local paper here in the Triangle) recently ran a great story on overuse injuries in young athletes. I firmly believe this is one of the fastest growing injuries I see in the clinic and in many cases it is preventable. One of the biggest issues now is this commonplace idea that gifted athletes should play the same sport year-round to get ahead.

I remember growing up as a kid and playing football, basketball and baseball in the fall, winter and spring. While AAU basketball and Legion ball existed, most kids were still playing multiple sports. Over my 15 years as a physical therapist I have witnessed several of these one sport stars see their playing time and bodies take a hit due to injury.

The American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) and the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) state that overuse injuries account for nearly half of the 2 million injuries seen among high school athletes each year. While soccer and swimming seem to send many athletes into PT, any repetitive throwing or overhead activity bears considerable risk for an eventual shoulder or elbow problem as well. Some of the common injuries I typically see are:

- Patellofemoral pain

- Shin splints

- Rotator cuff injury

- Bursitis

- Shoulder instability

- Little League elbow

Little League Elbow (medial epicondylar apophysitis)

These injuries are just some of the most common ones I see. In the article, the reporter focused on baseball and throwing. With that in mind, consider research published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine this past February from renowned surgeon James Andrews that revealed players who pitch more than 100 innings in a calendar year are 3.5 times more likely to be injured.

He goes on to say that “these injuries are the result of a system that prepares genetically gifted athletes to play at the highest levels, but eliminates most players because their bodies cannot withstand such intense activity at such an early age.” Sadly, he told the reporter that in 1998 he performed the Tommy John procedure on 5 kids high school age or younger, while in 2008 he did the same procedure on 28 children in the same age range. This injury is usually caused by throwing too much too soon.

Consider the following data on suggested pitch counts per game (source James Andrews, MD & Glenn Fleisig, MD):

- 8-10 y/o = 52 plus/minus 15 pitches

- 11-12 y/o = 68 plus/minus 18

- 13-14 y/o = 76 plus/minus 16

- 15-16 y/o = 91 plus/minus 16

- 17-18 y/o = 106 plus/minus 16

Unfortunately, I can personally relate to this blog post and story. I was a promising young pitcher up until the point I threw my arm out in travel baseball at age 13. The pain got so bad in my arm I could barely throw a ball 10 feet. I remember the orthopedic surgeon telling me that I could not throw again the rest of the summer. The pain (and memory of it) was so bad I elected to focus on position play and not to pitch again until my senior year of high school. At that point, my arm was no longer the same as I had missed three years of practice and development. Now, I too had become one of those kids whose body was never the same.

So, as a rehab and strength & conditioning professional, I want to help educate and promote better awareness to athletes, parents, coaches, trainers, AD’s, ATC’s and anyone who is involved in the care and training of young athletes. Fortunately, people are taking positive steps to reduce overuse injuries. One great initiative is STOP – Sports Trauma Overuse Prevention and you can learn more by clicking here to visit their website.

In the end, we must continue to educate everyone that the old motto of “No Pain, No Gain” is NOT the way to handle overuse injuries as this mentality may ruin the careers of young athletes or lead to an otherwise preventable injury and/or premature musculo-skeletal damage. Pain truly is a warning signal the body gives us to detect mechanical problems and make changes in our training/activity level until we sort out the cause and solution. I hope you will join me in supporting this mission and working hard at making sports fun, safe and free of overuse injuries for young athletes of all ages in the years to come.

References – The News & Observer – May 15, 2011