Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Often, people assume hip and knee pain begin and end in those respective joints. While this can be the case, the truth is the ankle may also have a say in the matter. In my practice, I often see gait deviations, IT band issues, patellofemoral pain and many other issues related to ankle stiffness or soleus issues.

In assessing athletes, runners and weekend warriors, I often pick up asymmetries when measuring closed chain ankle dorsiflexion. I have even observed people who have active dorsiflexion within normal limits while seated on a treatment table, but once they become weight bearing things change. Even small differences can dramatically affect the body as the brain will find a way to get the motion it needs to squat, run, lunge, etc.

This often involves a compensatory pattern at the knee and/or hip joint. So, to that end, I recommend several strategies to improve mobility. I am currently doing a three part series on this for PFP magazine to provide some effective exercises to improve ankle and soleus mobility. Click here to read the latest column.

Below is a sample video of the wall touches I use to improve ankle motion after mobilizing the soft tissue.

Typically, I advocate doing 1-2 sets 10-15 repetitions. Using the wall allows clients to have tactile feedback and a target to focus on. This is a simple, yet effective way to gain motion in a loaded closed chain fashion as the hip, knee and ankle flex together in running, landing, squatting, lunging, etc.

If you are curious how I assess side-to-side differences, click here to read my initial column on assessment. I hope these tools enhance your training and/or those you work with.

Unearthing the cause of anterior knee pain and ridding our patients and clients of it is one of the never ending searches for the “Holy Grail” we participate in throughout training and rehab circles. I honestly believe we will never find one right answer or simple solution. However, I do think we continue to gain a better understanding of just how linked and complex the body really is when it comes to the manifestation of knee pain and movement compensations.

We used to say rehab and train the knee if the knee hurts. It was simply strengthen the VMO and stretch the hamstrings, calves and IT Band. Slowly, we began looking to the hip as well as the foot and ankle as culprits in the onset of anterior knee pain. The idea of the ankle and hip joint needing more mobility to give the knee its desired level of stability has risen up and seems to have good traction these days.

Likewise, therapists and trainers have known for some time that weak hip abductors play into increased femoral internal rotation and adduction thereby exposing the knee to harmful valgus loading. So, clam shells, band exercises and leg raises have been implemented to programs across the board.

Single Leg Resisted Hip External Rotation

As a former athlete who has tried his hand at running over the past 5 years, I have increasingly studied, practiced and analyzed the use and importance of single leg training and its impact on my performance and injuries. As I dive deeper into this paradigm, I continue to believe and see the benefits of this training methodology for all of my athletes (not just runners).

As a therapist and strength coach, it is my job to assess movement, define asymmetries and correct faulty neuromuscular movement patterns. To that end, I have developed my own assessments, taken the FMS course, and increasingly observed single leg strength, mobility, stability and power in the clients I serve. Invariably, I always find imbalances – some small and some large ones.

What are some of the most common issues I see?

It is common knowledge in the medical community that treating patellofemoral joint pain (PFJP) is one of the most frustrating and difficult tasks to complete as there appears to be no standard way to do so. While clinicians strive to find the right recipe or protocol (I don’t believe there is just one by the way), researchers press on to find more clues.

A new article released in the April 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy seeks to bring clarification to a particular exercise pattern commonly used in rehab circles. The three exercises they looked at were:

- Forward step-up

- Lateral step-up

- Forward step-down

In the study, the authors looked at 20 healthy subjects (ages 18-35 and 10 males/females) performing the separate tasks with motion analysis, EMG and a force plate. The goal was to quantify patellofemoral joint reaction force (PFJRF) and patellofemoral joint stress (PFJS) during all three exercises with a step height that allowed a standard knee flexion angle of 45 degrees specific to each participant.

Key point: Previous research has been done to indicate that in a closed chain setting, knee flexion beyond 60 degrees leads to increased patellofemoral joint compression and this may be contraindicated for those with PFJ pain or chondromalacia. Also keep in mind that most people with PFJ complain of more pain descending stairs than ascending stairs.

In the study, the participants performed 3 trials of 5 repetitions of each exercise at a cadence of 1/0/1 paced with a metronome. The order of testing was randomized for each person. The authors used a biomechanical model to quantify PFJRF and PFJS consisting of knee flexion angle, adjusted knee extensor moment, PFJ contact area, quadriceps effective lever arm, and the relationship b/w quadriceps force and PFJRF.

Now on to the results……

So, have you ever experienced pain in the buttock that radiates down into the thigh? Maybe even felt some numbness and tingling? Recently, I was contacted by an experienced marathoner who has been plagued by pain in the buttock and posterior thigh. He self diagnosed himself as having piriformis syndrome after doing some research on the Internet. So. what is piriformis syndrome?

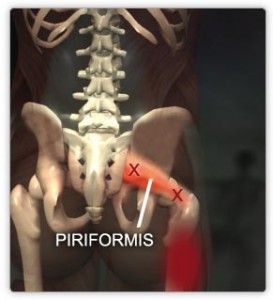

Some experts debate whether it truly exists, but essentially, it involves the piriformis, a small pear shaped muscle in that helps externally rotate (turn out) the hip and the sciatic nerve which runs down the entire back of the leg and is responsible for sensation and motor movement patterns of many of the muscles in the lower leg.

It is suggested that in this syndrome the sciatic nerve essentially becomes compressed or irritated by a tight piriformis muscle. The sciatic nerve travels above, below or even through the piriformis muscle itself based on anatomical studies.

Some have even suggested that prolonged sitting with the hips turned out or sitting on a wallet can contribute to this problem. I even remember being told in PT school that it is more common in truck drivers. With that said, I think I can count on one, if not both hands the number of patients I have seen in 15 years that I truly believe had piriformis syndrome.

Now back to my runner. He began having pain in his left buttock and hamstring in late December after seeing a trigger point specialist who suggested he had a tight piriformis and did some deep tissue work on it. A short time afterward, he began having symptoms. He saw a physical therapist for 2-3 sessions and was given some stretches to do. Meanwhile, he began getting deep tissue massage focused on the area in January and February.

Some people love their calves, while others hate them. Ever see people piling on the weight at the gym (barbells, seated calf press machine, etc.) attempting to build shapely calves? Or maybe you see people performing calf raises on a box with their feet in, straight ahead and out. The question has long been this: is there any real benefit to doing them beyond the neutral or straightforward position to get maximal activation and strength gains?

Why is this important? Well, beyond muscle tone, this question has physiological ramifications with respect to performance and rehabilitation. Consider, for example that as knee flexion angles increase, the medial gastroc becomes increasingly disadvantaged regardless of the ankle position. This suggests inherent functional differences in the muscle architecture and activation patterns of the medial and lateral heads of the gastroc.

In a study just published in the March 2011 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, Riemann et al. investigated the impact of all three positions on gastroc activation. They used 20 healthy subjects (10 male and 10 female) with no history of a calf injury and all had prior resistance training experience.