Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Many athletes and clients struggle with hamstring muscle activation. A normal quad to hamstring ratio would be 3:2, but studies often find that subjects tend to be closer to 2:1 (especially females). This diminished ratio can increase knee injury risk (non-contact ACL) with jumping and cutting sports. Some people struggle with proximal hamstring tendinopathy related to overuse. Incorporating eccentric hamstring exercises in your training can markedly improve hamstring strength and activation patterns.

Quad/Ham dynamic relationship

Execution: Begin in supine with 90 degrees of knee flexion and the feet flat on the floor. Next, bridge up into a table top position. Then, slowly begin to walk the feet out keeping the weight on the heels in an alternating pattern. Move the feet as far away from the body as possible while maintaining a good static bridge position.

Once form starts to falter or fatigue sets in, walk the feet back in using the same cadence and incremental steps until the start position is achieved. Perform 5 repetitions and repeat 2-3 times. Focus on control while avoiding pelvic rotation, and be cautious working into too much knee extension to avoid poor form or cramping.

This is an excellent way to improve hamstring strength while emphasizing pelvic stability. This exercise should be preceded by static bridging to ensure the client understands how to maintain a neutral pelvic position (consider using a half roll or towel as a visual aid to cue him/her out of rotational movement initially). The walk out exercise can be implemented as part of ACL prevention/rehab programs and also works well for runners and athletes struggling with hip/pelvic stability, proximal tendinopathy and general posterior chain weakness.

Regression: Bridge up and march in place for repetitions or time to develop sufficient strength and stability.

Progression: Increase repetitions or slow the cadence down pausing longer at each step to increase time under tension. Additionally, move the hands from palm down to palm up to reduce stability. For advanced clientele, the arms could be crossed with the hands resting on the opposite shoulder.

This post is the third corrective exercise in a series I am doing for Personal Fitness Professional Magazine in my online column titled “Functionally Fit.” To read more online exercise tips, visit www.fit-pro.com.

The hurdle step assessment (as part of the FMS) is designed to challenge the body’s proper stepping and stride mechanics as well as stability & control in single leg stance. The step leg must perform ankle DF and hip/knee flexion while core stability must be present in single leg stance.

Limited hip mobility and/or poor hip and core stability restricts natural movement and leads to compensatory motion often in the form of unwanted hip rotation, hip hiking, trunk sway in the frontal and sagittal plane. A common corrective exercise prescribed to improve core stability is a standing march (single leg stance) with straight arm pulling to engage the core.

Execution: Begin standing with the feet together while holding the cable handles with the palms down. Select a weight that provides ample enough resistance to maintain isometric shoulder extension for 30-60 seconds. Be careful not to select too little or too much weight as this will disrupt the execution of the exercise.

Next, pull the arms down toward the side and hold in that position. Maintaining an erect posture, slowly lift the left leg up (ankle dorsiflexion with knee and hip flexion) and pause for 2-3 seconds. Move the unsupported leg back to the start position but keep the arms actively extended. Repeat this sequence for 10 times on the left leg. Rest for 30-60 seconds and then repeat on the other leg. Perform 2 sets.

Additional notes: I tend to focus on unilateral consecutive repetitions (as described above) especially if there is a 2/1 asymmetry with the hurdle step. As the asymmetry is resolving, I will progress to a reciprocal pattern as this is more natural in life/sport. If a cable column is unavailable, alternate methods include using a suspension training apparatus or resistance tubing anchored high enough to accomplish the same upper body isometric pulling.

Application: Poor hip stability and control in single leg stance is a common cause of overuse injuries in runners and contributes to increased risk for anterior knee pain and ACL injuries. Keep in mind that poor performance on the hurdle step movement can be related to weak hip flexors on the stepping leg, tight hip flexors on the stance leg, diminished hip stability and poor balance.

It is critical to assess the whole movement prior to assuming that there is just one problem or weak link in the kinetic chain. Restoring symmetric, optimal stepping patterns will promote proper hip disassociation, as well as training the body to synergistically activate core and hip musculature to demonstrate optimal single leg stability in unilateral stance.

I work with lots of patients and clients who consistently demonstrate inadequate hip and core stability. I see this show up routinely as asymmetrical 1’s for the trunk stability push-up, in-line lunge, hurdle step and rotary stability movements on the FMS. Unfortunately, this has been a recurring them in many of my females recovering from ACL reconstruction as well as runners with persistent pain/dysfunction in one lower extremity.

I am always looking for better ways to train the body in whole movement patterns as well as functional positions. One of my preferred positions is to test and challenge my clients in a split squat position. I begin with an isometric split squat cueing proper alignment and muscle activation. As clients master isometric postural control, I will allow them to add an isotonic movement by squatting in the position.

As they progress, I will add in perturbations to stimulate changes or challenges to their center of gravity. Often, you will see them struggle much more on the involved side. But to be honest, I find most people have an incredibly hard time maintaining proper alignment for long without cheating or falling forward or to the side. Allowing clients to lose form is okay provided they are cued to fix their alignment or they naturally self correct.

An additional wrinkle I throw in for this training is using the BOSU Balance Trainer. Below is a video that shows how I use this progressing from shin down to just the toes as a support on the trail leg. The second version will burn up your clients’ thighs and quickly become one of their least favorite exercises. The great thing is that you do not have to offer much resistance to create a significant perturbation.

For more detail on this exercise and application, click here to read my PFP column featuring it this week.

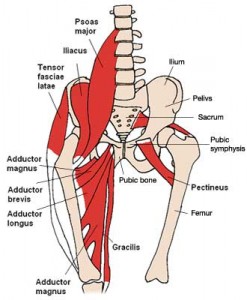

While I treat a vast number of knee ailments in my practice, the focus of my training and rehab is often more proximally directed at the hip. Understanding the role of hip muscles and how the hips and pelvis work together to impact knee alignment and closed chain function is critical in resolving knee pain and dysfunction.

Below is a “go to exercise” exercise I use for gluteus medius activation and core/pelvic stability training. Using a mini-band provides an adduction force cueing the client to abduct and activate their external rotators to maintain proper alignment. Additionally, they need to avoid a drop on one side of the pelvis (look at the ASIS).

Click here to read my entire column dedicated to this exercise in PFP’s online magazine. I hope you find this exercise and information useful for you and/or your clients.

I have been a bit behind on blogging as of late. I try to aim for one per week, but I also strive to deliver sound and relevant content. Additionally, I do not seek outside contributors so finding time to write can be tricky with work and family life too. So, forgive me for any apparent inconsistency in posting. Just know that I will always try to provide valuable content. Today’s post centers around an article in the July 2012 edition of AJSM.

My work at the Athletic Performance Center has provided me an increased opportunity to work with FAI and athletic hip injuries. This is an area of evolution and growth in our field, so I find it particularly interesting to see rationale and thought processes centering around the timing, contribution and selection of hip exercises for active patients/athletes.

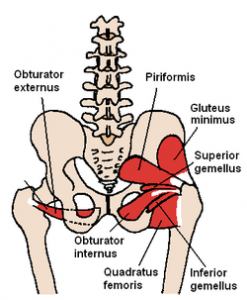

This article comes from the Steadman Philippon Research Institute in Vail, CO. The purpose of the study was to measure the highest activation of the piriformis and pectineus muscle during various exercises. The hypothesis was that highest pectineus activation would occur with hip flexion and moderate activity with internal rotation, whereas the highest activation with the piriformis would be with external rotation and/or abduction.

Methods: 10 healthy volunteers completed the following 13 exercises:

- Standing stool hip rotation

- Supine double leg bridge

- Supine single leg bridge

- Supine hip flexion

- Side-lying hip ABD with external rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD with internal rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD against a wall

- Hip clam exercise with hips in 45 degrees of flexion

- Hip clam exercise with hips in neutral

- Prone heel squeeze

- Prone resisted terminal knee extension

- Prone resisted knee flexion

- Prone resisted hip extension

All of these exercises have been reported to be used in hip rehab following arthroscopy or recovery from injury. The exercises were executed slowly and methodically with a metronome to reduce EMG amplitude variations.