Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Over the years, I have been fortunate to work with lots of athletes ranging from youth to professionals. Regardless of age or skill level, I have observed that each one approaches the recovery in their own way. Some are eager to tackle therapy, while others are apprehensive and fearful.

To be clear, the mindset of the patient is as important, if not more important than the physical part of the process as it relates to success. With ACL rehab, I pay close attention at post-op visit number one to determine if the patient is a coper, non-coper or somewhere in between. Having this awareness is crucial as I look to encourage the client and position him/her for success in the fist phase of rehab. The mindset of a patient recovering from their second or third ACL tear may differ greatly than that of a first timer.

With that said, assessing the state of mind of any athlete in the PT clinic is a must. An athlete’s identity, confidence and self-worth is often tied to his/her sport. Injuries separate the athletes from their teams and take away something very important to them. This can lead to depression, anxiety, anger, fear and loneliness to name a few.

It is imperative to connect with an athlete in the first 1-2 visits of rehab. I aim to bond with them and ensure they know I will do everything in my power to get them back to their prior level of performance. Fear of loss is powerful, and I want to partner with them to prevent the loss of playing time as quickly and safely I can though proper rehab.

As a sports medicine professional and physical therapist working with lots of athletes after ACL surgery, I am always looking for ways to improve post-op rehab and prevent a subsequent ACL injury. While we have lots of research looking at neuromuscular, genetic, sex and morphologic risk factors, we have not been able to make significant progress in injury reduction. So many athletes suffer the dreaded “pop” making a simple athletic maneuver they have done a thousand times before.

Based on nearly 19 years of experience training and rehabbing athletes from youth to professionals, I see strong links to a genetic predisposition (family history and prior injury) as well as concerns over neural fatigue. We already know the age of injury is a significant as research indicates those tearing at a younger age (around 20-21 y/o) are more likely to suffer a second injury. But what we know less about is the impact of ankle biomechanics (namely limited dorsiflexion) and how proximal weakness in the hip affects injury risk.

The latter topic was the focus of a study just published in the current edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine. In this prospective study, researchers sought to determine if baseline hip strength can predict future non-contact ACL tears in athletes.

Perhaps one of the most researched topics is ACL injuries. I have been studying and working for years in my clinical practice to find the best ways to rehab athletes following injury as well as implement the most effective injury prevention strategies. Prior studies indicate prevention programs even when self directed can be successful.

However, on the whole injury rates have not declined over the past decade or so. Much attention has been given to valgus landing mechanics, poor muscle firing, stiff landings, genetic difference between males and females, ligament dominance, quad dominance, and so forth. The predominant thoughts today for prevention center around neuromuscular training and eliminating faulty movement patterns (refer to work being done by Timothy Hewett and Darin Padua).

We also know from a biomechanical standpoint that the hamstrings play an integral role in preventing excess anterior tibial translation, and as such hamstring strengthening needs to be a big part of the rehab and prevention program. I believe in hamstring training that allows for activation in non-weaightbearing and weight bearing positions. Common exercises I will use include:

- HS bridging patterns (double /single leg, marching, knee extension, stability ball)

- Nordic HS curls

- HS curls (stability ball, TRX or machine)

- Sliders – focus on slow eccentric motion moving into knee extension followed by simultaneous curls/bridge

- Single leg RDL (add dumbbells or kettle bells for more load)

Note: click on any of the thumbnail images above for a full view of the exercise. From left to right: Nordic HS curls, sliding hamstring curls and single leg RDL).

A recent blog post entry by the UNC Department of Exercise and Sport Science (@UNCEXSS) has spurred my post today. Click here to read their entry on optimizing injury prevention based on work done by Professor Troy Blackburn regarding the effect of isometric and isotonic training on hamstring stiffness and ACL loading mechanisms. The research that was done holds promise for hamstring training designed to increased musculotendinous stiffness (MTS).

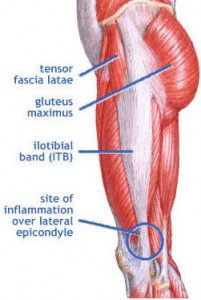

So, a very common issue I see in runners is iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome. In a nutshell, it involves excessive rubbing or friction of the ITB along the greater trochanter or lateral femoral epicondyle. It is more common along the lower leg just above the knee and typically worsens with increasing mileage or stairs.

The ITB is essential for stabilizing the knee during running. Several factors may contribute to increased risk for this problem:

- Muscle imbalances (weak gluteus medius and deep hip external rotators)

- Uneven leg length

- High and low arches

- Increased pronation leading to excessive tibial rotation = friction of the band

- Improper training progression

- Faulty footwear

- Poor running mechanics

- Limited ankle mobility (specifically dorsiflexion)

- Tightness in the tensor fascia latae (TFL) and glute max

Related information on this topic include a 2010 study published in JOSPT on competitive female runners with ITB syndrome:

Click here to see the abstract of the study

Click here to read an earlier blog post analysis of the above research article

Common signs and symptoms include stinging or nagging lateral knee pain that worsens with continued running. Hills and stairs may further aggravate symptoms. Some runners even note a “locking up” sensation that forces them to stop running altogether. How do I treat this?

I have been attending the 26th Annual Cincinnati Sports Medicine Advances on the Shoulder and Knee conference in Hilton Head, SC. This is my first time here and the course has not disappointed. I have always known that Dr. Frank Noyes is a very skilled surgeon and has a great group in Cincinnati as I am originally an Ohio guy too.

So, I thought I would just share a few little nuggets that I have taken away from the first three days of the course so far. I am not going into great depth, but suffice it to say these pearls shed some light on some controversial and difficult problems we see in sports medicine.

Shoulder Tidbits

- Fixing SLAP tears may not always fix shoulder pain as in many cases it may be in part due to posterior capsule tightness and anterior instability leading to internal impingement. Additionally, many of the docs here choose not to repair type 2 tears in those over 40 tears and provide a biceps tenotomy or tenodesis to instead to deliver more predictable pain relief as opposed to a labral repair.

- Intraoperative pain pumps in the shoulder are causing glenohumeral joint chondrolysis in the shoulder in many cases. According to the panel of docs, this has been seen in teenagers and patients in their twenties as well. They have often undergone other procedures from outside docs and then developed increasing pain afterward. Many have had to even undergo a total shoulder replacement after a few years post-op. The MDs here have suggested even post-operative Marcaine injections for pain relief in the shoulder should probably not be used. It was very sad to see an 18 y/o shoulder x-ray they put up that looked as if the patient was 80 years old.

- Double row rotator cuff tendon repairs seem to outperform single row repairs with respect to tendon healing (90% for DR and 76% for SR techniques in a comprehensive review of the literature)

- Stretching cross body horizontal adduction may be more important for throwers and overhead athletes than the sleeper stretch – best to have a therapist stabilize the scapula and then move the shoulder across the body keeping the shoulder in neutral rotation (it will tend to externally rotate)

- Arthroscopic stabilization is better than open surgery for posterior shoulder instability as the posterior cuff and deltoid are not violated, ROM recovery is more predictable, patient satisfaction is higher and there is a more predictable return to sport

Knee Tidbits

- Increased femoral anteversion and torsion is a developmental factor that does in fact control the knee to a great extent. The tibial tubercle-sulcus angle, thigh-foot angle and foot alignment is also key according to Dr. Lonnie Paulos. In cases of miserable patella mal-alignment, many will need de-rotation and re-alignment procedures to improve their symptoms.

- The consensus among the orthopods here was that using a bone-tendon-bone patella tendon autograft to reconstruct torn ACLs in the younger more active athletes (soccer players and football players) is preferable to a hamstring graft or allograft. Allografts did not seem to be the graft of choice by any of the docs for the younger patients. Some would use a hamstring autograft provided there was no MCL pathology. The PTG autograft was the gold standard for years (always my favorite graft choice for high level/demand athletes) so I was pleased to see the trend for this population moving away from the ST/gracilis HS grafts.

- Kevin Wilk, DPT (primary PT for Dr. James Andrews), was advocating restoring full and symmetrical ROM after ACL surgery. I tend to agree with this principle myself. However, Dr. Noyes was not in agreement and rather cautiously noted he would be okay with about 3 degrees of hyperextension on the repaired side no matter how much hyperextension was available on the other side. Kevin also noted that restoring full flexion was paramount to restoring running mechanics and speed in higher level athletes.

- The golden time to repair a MCL tear is in the first 7-10 days. Dr. Paulos also suggested it is absolutely necessary to fix the deep layer as well as the superficial layer. His talk emphasized how big of a mistake it is to not repair the deep layer. He also warns that the strength of the repair is less important than restoring proper length, tension and collagen.

- For PCL augmented repairs, a 2 bundle repair is repaired. Most of the docs like to use a quad tendon autograft from the contralateral thigh, but will take it from the same leg if patients insist. The consensus seemed to be that a repair should be done if there is 10 millimeters or more of drop off.

These are just some of the highlights I wanted to pass along. There was lots of other good stuff (much of it a nice review of anatomy, biomechanics and protocol guidelines for rehab) but I wanted to pass along some of these key items while they were fresh in my head. I will likely be sharing more in the future, particularly with respect to patello-femoral pain and SLAP tears as these are just so controversial in terms of surgical and rehab management.