Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

I have been a bit behind on blogging as of late. I try to aim for one per week, but I also strive to deliver sound and relevant content. Additionally, I do not seek outside contributors so finding time to write can be tricky with work and family life too. So, forgive me for any apparent inconsistency in posting. Just know that I will always try to provide valuable content. Today’s post centers around an article in the July 2012 edition of AJSM.

My work at the Athletic Performance Center has provided me an increased opportunity to work with FAI and athletic hip injuries. This is an area of evolution and growth in our field, so I find it particularly interesting to see rationale and thought processes centering around the timing, contribution and selection of hip exercises for active patients/athletes.

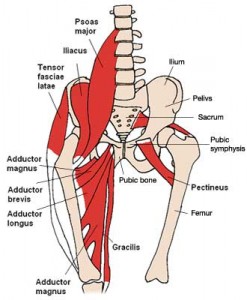

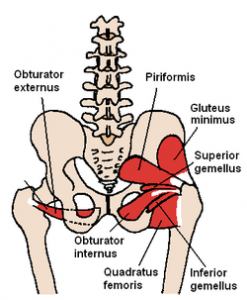

This article comes from the Steadman Philippon Research Institute in Vail, CO. The purpose of the study was to measure the highest activation of the piriformis and pectineus muscle during various exercises. The hypothesis was that highest pectineus activation would occur with hip flexion and moderate activity with internal rotation, whereas the highest activation with the piriformis would be with external rotation and/or abduction.

Methods: 10 healthy volunteers completed the following 13 exercises:

- Standing stool hip rotation

- Supine double leg bridge

- Supine single leg bridge

- Supine hip flexion

- Side-lying hip ABD with external rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD with internal rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD against a wall

- Hip clam exercise with hips in 45 degrees of flexion

- Hip clam exercise with hips in neutral

- Prone heel squeeze

- Prone resisted terminal knee extension

- Prone resisted knee flexion

- Prone resisted hip extension

All of these exercises have been reported to be used in hip rehab following arthroscopy or recovery from injury. The exercises were executed slowly and methodically with a metronome to reduce EMG amplitude variations.

Over the past several years, the trend in the health and fitness industry has been toward injury prevention and movement screening. Gray Cook and Lee Burton have given us the FMS. More recently, the Y-Balance test has emerged as another tool to assess asymmetry in the upper and lower quarter.

I am currently FMS certified and planning to attend the SFMA course next month in Durham. I routinely incorporate the FMS in both our rehab and sports performance work at the APC. I like many things about the screening exam. It provides a consistent tool to assess baseline movement and record asymmetry on a simple 4 point scale scale. It also has been shown to have good intra and inter-rater reliability. Click here for a recent study published in the Journal or Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

For those unfamiliar with the screen, it is 7 tests scored on a 0-3 scale as follows:

- 0 = pain

- 1 = unable to perform the movement pattern (or perform with marked dysfunction)

- 2 = performs the movement with a mild compensation

- 3 = performs the movement correctly

I would say on average, most of the athletes I screen score between a 12 and 15. My highest score was a 19 (9 year old gymnast) and my lowest was a 9 (NFL lineman). As screeners, we are charged with uncovering asymmetry and faulty movement patterns. What do you see in the following picture?

Clearly, the dowel is not level, thus we score it a 2. She also had some ER in the right leg when stepping over the hurdle. She was a symmetrical 2 on the hurdle step test. This is a Division I soccer player who scored 17 on the exam.

Most of the movements seem straightforward. However, many question what the rotary stability test measures with respect to the ideal 3 score (ipsilateral movement)? It assesses an unnatural movement pattern to be sure. This athlete failed miserably on the ipsilateral pattern but scored a solid 2 with the contralateral pattern.

I have yet to test someone who can score a legitimate 3. I have seen some get a 3 on one side and 2 on the other (asymmetrical and a red flag in FMS land). As one who naturally questions things, I find myself questioning how many are truly capable of scoring a 3.

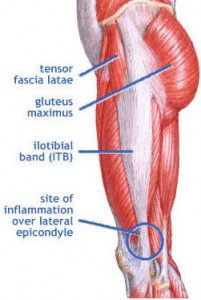

So, a very common issue I see in runners is iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome. In a nutshell, it involves excessive rubbing or friction of the ITB along the greater trochanter or lateral femoral epicondyle. It is more common along the lower leg just above the knee and typically worsens with increasing mileage or stairs.

The ITB is essential for stabilizing the knee during running. Several factors may contribute to increased risk for this problem:

- Muscle imbalances (weak gluteus medius and deep hip external rotators)

- Uneven leg length

- High and low arches

- Increased pronation leading to excessive tibial rotation = friction of the band

- Improper training progression

- Faulty footwear

- Poor running mechanics

- Limited ankle mobility (specifically dorsiflexion)

- Tightness in the tensor fascia latae (TFL) and glute max

Related information on this topic include a 2010 study published in JOSPT on competitive female runners with ITB syndrome:

Click here to see the abstract of the study

Click here to read an earlier blog post analysis of the above research article

Common signs and symptoms include stinging or nagging lateral knee pain that worsens with continued running. Hills and stairs may further aggravate symptoms. Some runners even note a “locking up” sensation that forces them to stop running altogether. How do I treat this?

So, I treat a number of fitness enthusiasts in the clinic and many include Crossfit clients. Recently, I evaluated a 38 y/o male on 2/16/12 with a 3 month history of right shoulder pain. He performs Crossfit workouts 6 days per week. His initial intake revealed:

- Constant shoulder pain that worsens with overhead movements

- Pain with bar hangs, overhead squats and wide grip snatches

- Unable to do kipping (only doing strict form pull-ups)

- Pain if laying on his right side at night

- No c/o neck pain, referred pain or numbness/tingling

Notice the shoulder position during the kipping pull-up and overhead squat below. This is a position of heightened risk for the shoulder.

His exam revealed the following:

- Normal range of motion

- Strength within normal limits except for supraspinatus and external rotation graded 3+/5 with pain

- Positive impingement signs

- Negative shrug sign

- Negative Speed’s and O’Brien’s test

- Tender along distal supraspinatus tendon

Based on the clinical exam, it was apparent he had rotator cuff inflammation and perhaps even a tear. Keep in mind he had not seen a physician yet. I began treatment focused on scapular stabilization and rotator cuff strengthening as well as pec and posterior capsule stretching to address the impingement. Ultrasound and cryotherapy were used initially to reduce pain and inflammation.

One month following the eval

By 3/14/12, his pain was resolved with daily activity and he had returned to snatches and push-press exercises without pain. He still could not do overhead squats with the Olympic bar pain free, but he could with a pvc pipe. Strength was now 4/5 for supraspinatus and 4+/5 for external rotation. All impingement tests were now negative as were Speed’s and O’Brien’s testing.

One of the most common issues I see in the clinic with active exercise enthusiasts between the age of 20 and 55 is shoulder pain. Weightlifting has been popular for ages, but Crossfit is all the rage these days. Both disciplines involve overhead lifts. The key thing to remember when performing overhead repetitive lifts is how load and stress not only affects strength and power, but how it impacts the joint itself.

Pull-ups and pull-downs are staples for most clients I see. As a therapist and strength coach, I am always thinking and analyzing how variables such as grip, grip width, arm position, scapular activation, trunk angles etc influence exercise and how force is absorbed by the body. One such exercise I have spent time studying and tweaking is the lat pull-down.

Consider for a moment how width and grip impacts the relative abduction and horizontal external rotation in the shoulder at the top and bottom of the movement in the pictures below (start and finish positions are vertically oriented):

It should be common knowledge for most, but I will state it for the record anyway – you should NEVER do behind the neck pull-downs. Beyond the horrible neck position, this places the shoulder in a dangerous position for impingement and excessively stresses the anterior shoulder capsule. A wider grip (be it with pull-ups, pull downs, push-ups) will always transfer more stress to the shoulder joint because you have a longer lever and greater abduction and horizontal external rotation.

So, what bearing does this have in relation to the rotator cuff and SLAP injuries? For more information and details on the application of the grip choice, click here to read the full column I did for PFP Magazine this month. Stay tuned for my next post (a follow-up to this one) one of my Crossfit patients who now only has pain with overhead squats and how my differential diagnosis and rehab has led me to conclude what is wrong with his shoulder. Keep in mind we must learn to train smarter so we can train harder and longer without pain and injury. Biomechanics and understanding your own body really does matter.