Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

I just finished presenting at our our second ACL Symposium of the year at the Athletic Performance Center last Saturday. Rehabbing and training female athletes has been a passion of mine for some time. Over the years, I have also developed a love for research and reading it, particularly studies on the ACL.

In my practice, I have incorporated jump landing, single leg training and deceleration based training for some time. While we all know females are 3-8 times more likely to suffer an ACL injury than males, we have not isolated the exact reason why. Researchers have offered some clues such as: wider pelvis, narrow femoral notch, smaller ACL, ligament dominance, limb dominance, natural laxity (hormonal factors), wider Q angles, and faulty muscle firing patterns to name a few.

Many of the structural factors are beyond our control. So, as practitioners, we must focus on the training. Consider the following study just published in the August 2011 edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine that basically reveals females develop peak valgus moments during deceleration during a drop landing maneuver, whereas males develop peak valgus forces during acceleration on the way back up:

Drop Landing

This article adds more evidence that females recruit and fire their muscles very differently than males. More importantly, it reiterates that we as coaches, therapists and S & C professionals need to be working on deceleration mechanics. I believe this starts with simple soft two legged drills such as:

- Small squat jump and holds

- Box drops and holds

- Forward line jump, stick and hold

- Lateral line jump, stick and hold

- 90 degree jump turn, stick and hold

In addition, one of my favorite drills is a single leg forward leap (hop) and stick working on deceleration. The athlete stands on the right leg and then pushes off forward landing on the left leg. Coaching the athlete to land softly on a bent hip and knee while avoiding valgus is important. I usually perform 2-3 sets of 5 reps on each side. Cueing with a mirror, auditory corrections and tactile cues are useful in encouraging proper form.

SL Stick (start)

SL Stick (finish)

It is important to keep in mind that the majority of non-contact ACL tears occur between 0 and 30 degrees of knee flexion. They also typically involve deceleration (landing, jump stop or change of direction), planting or cutting. For this reason, deceleration training must also involve programming for agility and change of direction.

On Saturday, I led the break-out session on deceleration training and covered a few key exercises I use with my athletes. These drills are layered on one another and the basic ones I begin with are:

- Stops – I have athletes accelerate out and then decelerate to a controlled two legged stop after 10-20 yards. Keep in mind allowing for a longer run will allow the athlete to gradually slow down, while decreasing the distance increases intensity and force on the knees. I coach breaking down with small “pitter patter” steps versus a sudden hard stop.

- 2 cone lateral shuffle stops – the athlete shuffles over 5-6 yards and then stops with good hip, knee and foot alignment working to keep the shoulders inside the knees (inside the box). I progress to multiple cone shuffles to increase intensity and maximize repetitive deceleration.

- Pro-agility drills – 3 cones are placed 5 yards apart and I combine linear and lateral movements between the cones layering #1 and #2 above in a continuous pattern to work on acceleration/deceleration combos and change of direction

- Y drill (4 cones) – the athlete runs forward to a cone 5-15 yards out and then performs a 45 degree cut left/right. The progression begins with directed and predictable movement and then advances to reactive cueing with auditory and visual cues.

- Arrow drill (4 cones) – The athlete runs 5-15 yards forward and then performs a 135 degree cut left/right and runs past the cone that serves as the bottom edge of the arrow head. This is much more demanding on the body (knee) and as such I only move to this after the Y drill has been mastered. In addition, I teach a hip turn (from Lee Taft) to reposition the hips and minimize torsion on the lower leg. I move from predictive to reactive agility as in the Y drill.

These exercises are a small sampling of my ACL prehab/rehab routine. I also include an enormous amount of single leg PRE’s and balance training as well. I believe the most important things we can currently do to reduce ACL risk in this population are:

- Screen our athletes to help identify risk (FMS, drop landing, dynamic strength,running/cutting analysis)

- Emphasize hamstring, gluteus medius and lateral rotator strengthening

- Teach landing mechanics and proper deceleration through neuromuscular exercise, biofeedback and repetitive cueing

- Refine proper cutting technique by teaching ideal angles and how to reposition the hips

- Empower coaches and athletes with simple yet effective body weight training routines that can be replicated on the field or court with the team

For now, the battle rages on. I hope you will join me in the quest to prevent these catastrophic injuries. I think as research evolves we will continue to see that the answer to promoting optimal stability at the knee will increasingly have more to do with addressing the hip and ankle. For now, we need to teach soft bent knee landing/cutting that shifts the body’s center of mass forward, while eliminating valgus loading as much as possible in the danger zone.

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is often a hidden and misunderstood cause of hip pain. I currently work with a physician who has studied under some of the best hip arthroscopists in the US, and he is performing arthroscopic procedures to resolve hip impingement. For many years, this has likely been a source of misdiagnosed, under treated and debilitating hip pain for people.

As things advance in medicine, hip arthroscopy is expanding and allowing for easier surgical correction of these issues. However, it is not an easy surgery technically speaking. As such, finding the right surgeon (if needed) is critical to attaining a positive outcome. Who normally gets it? Unfortunately, many people are predisposed to it, much like we see the natural genetic architecture (shape) of the acromion affecting impingement in the shoulder.

If you have an overhang of the hip acetabulum (socket) or non-spherical shape of the femoral head (or both) this can compromise the joint space and injure the joint cartilage and/or labrum. Destruction can occur at a very young age. I am currently rehabbing a 19 y/o male who recently underwent hip arthroscopy to debride his labrum and smooth out the hip socket and re-shape the femoral head. He had extensive damage at an early age due to his joint architecture and shows some signs of impingement on the other side as well.

How do you know if you have hip impingement? Generally, you may have hip joint pain along the front, side or back of the hip along with stiffness or a marked loss of motion (namely internal rotation). It is common in high level athletes and active individuals. However, other things may cause hip pain as well such as iliopsoas tendonitis, low back pain, SI joint pain, groin strain, hip dysplasia, etc. so a careful history, exam and plain films are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. If suspected, an MR athrogram is usually ordered to confirm if there are labral tears present. Physicians also use an injection with anesthetic to see if the pain is truly coming from the hip joint. This may be done under fluoroscopy to ensure it is in the joint space.

Signs and symptoms of FAI may include:

- Pain with sitting

- Pain or limited squatting

- Stiffness and decreased internal rotation

- Pain with impingement testing (see picture below of hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation – examiner will move the hip into this position and marked stiffness/loss of internal rotation and pain indicates a positive test)

Conservative treatment typically involves limiting or avoiding squats, strengthening the core and hip stabilizers as well as attempting to maximize mobility of the joint. Due to the fact that by the time pain brings patients in to see the doctor there has already been marked labral and joint damage, a cautious and proactive approach to managing hip pain is warranted especially in younger active patients and athletes.

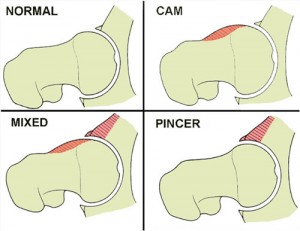

The types of lesions seen are either Cam or Pincer lesions.

Cam lesion – involves an aspherical shape of the femoral that causes abnormal contact between the ball and socket leading to impingement

Pincer lesion – involves excessive overgrowth of the acetabulum resulting in too much coverage of the femoral head and causing impingement where the labrum gets pinched

You can also see a mixed lesion where Cam and Pincer lesions are involved. FAI may lead or contribute to cartilage damage, labral tears, hyperlaxity, sports hernias, low back pain and early arthritis.

The good news is that these patients typically do well post-operatively. Dr. Philipon et al reported in 2007 in the Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. (click here to read the abstract) on 45 professional athletes who underwent arthroscopic management of FAI with an average follow-up of 1.6 years. In this time period 78% of them were able to return to their sport.

Following surgery, weight bearing may be restricted for the first 4 weeks or so to protect the labrum if it is repaired. With a simple debridement and re-contouring of the acetabulum, weight bearing may be initiated earlier. Avoiding twisting motions and excessive external rotation is a must in the first month or so as well. Typically, impact and twisting restrictions are lifted around 3 months post-op.

In the end, proper diagnosis and treatment is necessary to preserve the hip joint and maximize function and return to sport. If you or someone you know suffers from chronic and persistent hip pain that has failed conservative treatment, then consider getting a second look to rule out FAI.

By far the most comments on my blog and emails that flood my inbox these days have to do with SLAP tears. I must admit that outside of ACL tears and rotator cuff issues, I find myself increasingly drawn to studying and researching this issue. It definitely is a source of great pain for many and an issue that medical professionals are challenged by today.

In my personal clinical experience, I see good, bad and in between outcomes. Through email and my blog I tend to read more on the not so good side from people who are seeking my expertise in how to resolve their issues. When I speak to surgeons, I find they are often hesitant to commit to a set algorithm of treatment, and they are not 100% sure what the right answer is in addressing these injuries as a whole.

If you read the literature, the success in terms of patient satisfaction and return to premorbid activity levels is not going to make you rush down to the operating room and opt for an arthroscopic repair if you are an overhead athlete (especially baseball players). However, other studies have presented more favorable data ranging from 63%-75% good-excellent satisfaction in other overhead athletes who have had the procedure done.

If you are unfamiliar with SLAP tears, I suggest reading my original post on them (click here). In today’s post, I wanted to present a quick recap on Type II SLAP tears and some new published research on the results of revision procedures where the primary repair failed.

Below are two images of a type II tear (MRI and operative view from the scope)

Keep in mind a type II tear means the biceps anchor/superior labrum has pulled away from the glenoid with resulting instability of the complex. This is the most common type of tear seen among injured people. In a study from the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in LA in the latest American Journal of Sports Medicine (June 2011 – click here for the abstract), they discussed a chart review of from 2003-2009 looking at patients who had undergone revision type II SLAP repairs.

ACL injuries continue to proliferate among female athletes. I am passionate about preventing them, and part of my professional mission is to study and evolve in my rehab and prevention training approaches all the time to stay on top. I wanted to pass along some new information on a new screening tool just unveiled in the Strength and Conditioning Journal this month.

Before I reveal the screening and training tool, I want to take a moment and review what Timothy Hewett refers to as modifiable risk factors that contribute to injury risk based on his work:

- Ligament Dominance – defined as an imbalance b/w neuromuscular and ligamentous control of dynamic knee stability and it is visualized by loss of frontal plane control with landing and cutting

- Quadriceps Dominance – defined as an imbalance between quad and hamstring strength, recruitment and coordination

- Leg Dominance – defined as an imbalance between the two legs with respect to strength, coordination and control

- Trunk Dominance ‘Core’ Dysfunction – defined as an imbalance b/w the inertial demands on the trunk and its ability to resist or control/resist it

Previously, Hewett has identified that high knee abduction moments are related to high LOAD on the knee and a major risk factor for ACL injury. He and his colleagues have done extensive motion analysis in their lab in Cincinnati, OH. As such, a drop landing test has been used as one tool to observe landing mechanics and assign some risk value to athletes competing in cutting and jumping sports.

In the current article (click here for the abstract) Meyer, Brent, Ford and Hewett unveil a new screening tool involving the tuck jump. They propose that this tool is easier for the S & C coaches to do on the field and not only assess risk factors by way of observing technical flaws, but also use the tool as a training maneuver.

The idea is the subject will perform tuck jumps for 10 seconds consecutively while the observer makes notes on the following pre, mid and post jumping:

- Lower extremity valgus at landing

- Thighs do not reach parallel (peak height of jump)

- Thighs not equal side-to-side (during flight)

- Foot placement not shoulder width apart

- Foot placement not parallel (front to back)

- Foot contact timing not equal

- Excessive landing contact noise

- Pause b/w jumps

- Technique declines prior to 10 seconds

- Does not land in same footprint (excessive in flight motion)

Factors 1-3 refer to knee and thigh motion, 4-7 refer to foot position during landing and 8-10 refer to plyometric technique. Coaches are instructed to grade the flaws if seen with check marks during the phases they are seen and use this as a guide for correction. They may also use cameras in the frontal and sagittal plane to assist them.

My thoughts on this are:

- There is sound science behind the rationale for the test and modifiable risk factors

- There is a need for basic no-cost screening tools coaches can apply in their settings

- The tuck jump assessment will provide instant feedback on form and identify technical flaws that may indicate higher risk for injury

- The tuck jump is a higher demand plyo drill so I fear poor form may be as much to blame on inexperience and unrefined motor patterns as it is to just dominance patterns so we need to keep plyo training experience in mind when analyzing the screen results especially for beginners

- The tuck jump assessment does not really consider fundamental movement restrictions that may bias the form on one side if an asymmetry is present

- I still wonder how much ankle pronation impacts landing and whether we will see more research on this – there was a study done at ECU where they used orthotics and saw a reduction in ACL tears in their collegiate athletes so I have to wonder about this crucial element of the kinetic chain

In the end, we still lack many answers. According to data published in the Journal of Athletic Training in 2006, non targeted neuromuscular training programs need to be applied to 89 female athletes to prevent 1 ACL tear. So, we need to keep studying and applying science to our training, all the while critically questioning science and looking at our athletes holistically to find the best prevention strategies for each one individually and for at risk athletes as a whole.

I have been attending the 26th Annual Cincinnati Sports Medicine Advances on the Shoulder and Knee conference in Hilton Head, SC. This is my first time here and the course has not disappointed. I have always known that Dr. Frank Noyes is a very skilled surgeon and has a great group in Cincinnati as I am originally an Ohio guy too.

So, I thought I would just share a few little nuggets that I have taken away from the first three days of the course so far. I am not going into great depth, but suffice it to say these pearls shed some light on some controversial and difficult problems we see in sports medicine.

Shoulder Tidbits

- Fixing SLAP tears may not always fix shoulder pain as in many cases it may be in part due to posterior capsule tightness and anterior instability leading to internal impingement. Additionally, many of the docs here choose not to repair type 2 tears in those over 40 tears and provide a biceps tenotomy or tenodesis to instead to deliver more predictable pain relief as opposed to a labral repair.

- Intraoperative pain pumps in the shoulder are causing glenohumeral joint chondrolysis in the shoulder in many cases. According to the panel of docs, this has been seen in teenagers and patients in their twenties as well. They have often undergone other procedures from outside docs and then developed increasing pain afterward. Many have had to even undergo a total shoulder replacement after a few years post-op. The MDs here have suggested even post-operative Marcaine injections for pain relief in the shoulder should probably not be used. It was very sad to see an 18 y/o shoulder x-ray they put up that looked as if the patient was 80 years old.

- Double row rotator cuff tendon repairs seem to outperform single row repairs with respect to tendon healing (90% for DR and 76% for SR techniques in a comprehensive review of the literature)

- Stretching cross body horizontal adduction may be more important for throwers and overhead athletes than the sleeper stretch – best to have a therapist stabilize the scapula and then move the shoulder across the body keeping the shoulder in neutral rotation (it will tend to externally rotate)

- Arthroscopic stabilization is better than open surgery for posterior shoulder instability as the posterior cuff and deltoid are not violated, ROM recovery is more predictable, patient satisfaction is higher and there is a more predictable return to sport

Knee Tidbits

- Increased femoral anteversion and torsion is a developmental factor that does in fact control the knee to a great extent. The tibial tubercle-sulcus angle, thigh-foot angle and foot alignment is also key according to Dr. Lonnie Paulos. In cases of miserable patella mal-alignment, many will need de-rotation and re-alignment procedures to improve their symptoms.

- The consensus among the orthopods here was that using a bone-tendon-bone patella tendon autograft to reconstruct torn ACLs in the younger more active athletes (soccer players and football players) is preferable to a hamstring graft or allograft. Allografts did not seem to be the graft of choice by any of the docs for the younger patients. Some would use a hamstring autograft provided there was no MCL pathology. The PTG autograft was the gold standard for years (always my favorite graft choice for high level/demand athletes) so I was pleased to see the trend for this population moving away from the ST/gracilis HS grafts.

- Kevin Wilk, DPT (primary PT for Dr. James Andrews), was advocating restoring full and symmetrical ROM after ACL surgery. I tend to agree with this principle myself. However, Dr. Noyes was not in agreement and rather cautiously noted he would be okay with about 3 degrees of hyperextension on the repaired side no matter how much hyperextension was available on the other side. Kevin also noted that restoring full flexion was paramount to restoring running mechanics and speed in higher level athletes.

- The golden time to repair a MCL tear is in the first 7-10 days. Dr. Paulos also suggested it is absolutely necessary to fix the deep layer as well as the superficial layer. His talk emphasized how big of a mistake it is to not repair the deep layer. He also warns that the strength of the repair is less important than restoring proper length, tension and collagen.

- For PCL augmented repairs, a 2 bundle repair is repaired. Most of the docs like to use a quad tendon autograft from the contralateral thigh, but will take it from the same leg if patients insist. The consensus seemed to be that a repair should be done if there is 10 millimeters or more of drop off.

These are just some of the highlights I wanted to pass along. There was lots of other good stuff (much of it a nice review of anatomy, biomechanics and protocol guidelines for rehab) but I wanted to pass along some of these key items while they were fresh in my head. I will likely be sharing more in the future, particularly with respect to patello-femoral pain and SLAP tears as these are just so controversial in terms of surgical and rehab management.