Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is often a hidden and misunderstood cause of hip pain. I currently work with a physician who has studied under some of the best hip arthroscopists in the US, and he is performing arthroscopic procedures to resolve hip impingement. For many years, this has likely been a source of misdiagnosed, under treated and debilitating hip pain for people.

As things advance in medicine, hip arthroscopy is expanding and allowing for easier surgical correction of these issues. However, it is not an easy surgery technically speaking. As such, finding the right surgeon (if needed) is critical to attaining a positive outcome. Who normally gets it? Unfortunately, many people are predisposed to it, much like we see the natural genetic architecture (shape) of the acromion affecting impingement in the shoulder.

If you have an overhang of the hip acetabulum (socket) or non-spherical shape of the femoral head (or both) this can compromise the joint space and injure the joint cartilage and/or labrum. Destruction can occur at a very young age. I am currently rehabbing a 19 y/o male who recently underwent hip arthroscopy to debride his labrum and smooth out the hip socket and re-shape the femoral head. He had extensive damage at an early age due to his joint architecture and shows some signs of impingement on the other side as well.

How do you know if you have hip impingement? Generally, you may have hip joint pain along the front, side or back of the hip along with stiffness or a marked loss of motion (namely internal rotation). It is common in high level athletes and active individuals. However, other things may cause hip pain as well such as iliopsoas tendonitis, low back pain, SI joint pain, groin strain, hip dysplasia, etc. so a careful history, exam and plain films are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. If suspected, an MR athrogram is usually ordered to confirm if there are labral tears present. Physicians also use an injection with anesthetic to see if the pain is truly coming from the hip joint. This may be done under fluoroscopy to ensure it is in the joint space.

Signs and symptoms of FAI may include:

- Pain with sitting

- Pain or limited squatting

- Stiffness and decreased internal rotation

- Pain with impingement testing (see picture below of hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation – examiner will move the hip into this position and marked stiffness/loss of internal rotation and pain indicates a positive test)

Conservative treatment typically involves limiting or avoiding squats, strengthening the core and hip stabilizers as well as attempting to maximize mobility of the joint. Due to the fact that by the time pain brings patients in to see the doctor there has already been marked labral and joint damage, a cautious and proactive approach to managing hip pain is warranted especially in younger active patients and athletes.

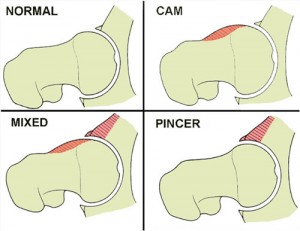

The types of lesions seen are either Cam or Pincer lesions.

Cam lesion – involves an aspherical shape of the femoral that causes abnormal contact between the ball and socket leading to impingement

Pincer lesion – involves excessive overgrowth of the acetabulum resulting in too much coverage of the femoral head and causing impingement where the labrum gets pinched

You can also see a mixed lesion where Cam and Pincer lesions are involved. FAI may lead or contribute to cartilage damage, labral tears, hyperlaxity, sports hernias, low back pain and early arthritis.

The good news is that these patients typically do well post-operatively. Dr. Philipon et al reported in 2007 in the Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. (click here to read the abstract) on 45 professional athletes who underwent arthroscopic management of FAI with an average follow-up of 1.6 years. In this time period 78% of them were able to return to their sport.

Following surgery, weight bearing may be restricted for the first 4 weeks or so to protect the labrum if it is repaired. With a simple debridement and re-contouring of the acetabulum, weight bearing may be initiated earlier. Avoiding twisting motions and excessive external rotation is a must in the first month or so as well. Typically, impact and twisting restrictions are lifted around 3 months post-op.

In the end, proper diagnosis and treatment is necessary to preserve the hip joint and maximize function and return to sport. If you or someone you know suffers from chronic and persistent hip pain that has failed conservative treatment, then consider getting a second look to rule out FAI.

It is no secret that Americans are trying to stay more active well into their baby boomer years and beyond. The million dollar question is how will what you do today affect your joints down the road.

Scholars, scientists and medical experts do not seem to agree 100% on what is too much, but most tend to agree that excessive running, obesity, irregular or unusually intense activity (think weekend warriors here), muscular weakness and even decreased flexibility may all contribute to arthritis.

The New York Times recently ran a story about the cost of total joint replacement and suggestions on how people can be proactive to reduce the risk and debilitating effects of arthritis. Click here to read the article.

I think one of the most amusing yet ironic things about science is that it often contradicts itself. Obviously, we know being overweight increases stress on the load bearing joints. Most people would also knowingly acknowledge that improved strength and flexibility would make for healthier knees and hips.

The big question mark for me is impact loading, or simply the argument of whether to run or not to run. Some docs say no way. Others say yes. Yet others offer more ambiguous words on the subject. So, what do I think?

I honestly believe there may be no absolute answer. I am not convinced running on a treadmill is all that much better for you as some would suggest either. My body tells me blacktop surfaces are better than cement sidewalks, while the soft earth is better yet still. I use the treadmill in the winter and for speed work but if you run events too much treadmill work will let you down on race day as the body is ill prepared.

Much like exercise prescription, I think joint loading and tolerance is a very individual matter indeed. Biomechanics, posture, training history, medical history, repetitive movements, footwear, nutrition, body type, recovery, etc are just a few of the variables one must consider when passing judgment on exercise prescription and limits.

Beyond that, the best indication to reduce or remove an activity for a short bit or long term is obviously pain. But before doing so, one must correctly identify the source of the pain. At times, the pain may seem like a joint issue when in fact it could simply stem from poor muscle recruitment, lack of mobility or faulty movement patterns thereby subjecting joints to undue stress.

I say all this to say we must be careful in saying one should not do something definitively. Some folks run well into their 80’s without issues. Others break down after one endurance event. In the end, we must face facts. The human body is complex and no two people are exactly alike. I had left hip pain years ago that felt like arthritis. My orthopd told me the x-ray showed a few mild bone spurs and mild hip dysplasia.

His advice? Quit running. I did for 6 months and the pain did not subside. So, I began a progressive running program and changed up my strength training to more single leg based work. Guess what? My pain went away 100%. This tells me the impact itself was not likely the cause of my pain, but more likely a muscle imbalance that I overcame through more efficient strength training.

We must look at science, anecdotal findings and clinical experience to pull out general patterns and thoughts all the while continuing to use assessment, feedback and results to lead us to the best conclusion for each client, patient or athlete. You must use all this information to make the best decision for your situation as well.