Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is often a hidden and misunderstood cause of hip pain. I currently work with a physician who has studied under some of the best hip arthroscopists in the US, and he is performing arthroscopic procedures to resolve hip impingement. For many years, this has likely been a source of misdiagnosed, under treated and debilitating hip pain for people.

As things advance in medicine, hip arthroscopy is expanding and allowing for easier surgical correction of these issues. However, it is not an easy surgery technically speaking. As such, finding the right surgeon (if needed) is critical to attaining a positive outcome. Who normally gets it? Unfortunately, many people are predisposed to it, much like we see the natural genetic architecture (shape) of the acromion affecting impingement in the shoulder.

If you have an overhang of the hip acetabulum (socket) or non-spherical shape of the femoral head (or both) this can compromise the joint space and injure the joint cartilage and/or labrum. Destruction can occur at a very young age. I am currently rehabbing a 19 y/o male who recently underwent hip arthroscopy to debride his labrum and smooth out the hip socket and re-shape the femoral head. He had extensive damage at an early age due to his joint architecture and shows some signs of impingement on the other side as well.

How do you know if you have hip impingement? Generally, you may have hip joint pain along the front, side or back of the hip along with stiffness or a marked loss of motion (namely internal rotation). It is common in high level athletes and active individuals. However, other things may cause hip pain as well such as iliopsoas tendonitis, low back pain, SI joint pain, groin strain, hip dysplasia, etc. so a careful history, exam and plain films are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. If suspected, an MR athrogram is usually ordered to confirm if there are labral tears present. Physicians also use an injection with anesthetic to see if the pain is truly coming from the hip joint. This may be done under fluoroscopy to ensure it is in the joint space.

Signs and symptoms of FAI may include:

- Pain with sitting

- Pain or limited squatting

- Stiffness and decreased internal rotation

- Pain with impingement testing (see picture below of hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation – examiner will move the hip into this position and marked stiffness/loss of internal rotation and pain indicates a positive test)

Conservative treatment typically involves limiting or avoiding squats, strengthening the core and hip stabilizers as well as attempting to maximize mobility of the joint. Due to the fact that by the time pain brings patients in to see the doctor there has already been marked labral and joint damage, a cautious and proactive approach to managing hip pain is warranted especially in younger active patients and athletes.

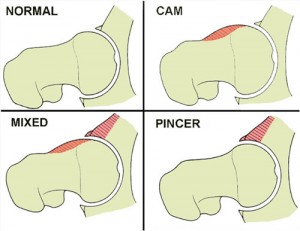

The types of lesions seen are either Cam or Pincer lesions.

Cam lesion – involves an aspherical shape of the femoral that causes abnormal contact between the ball and socket leading to impingement

Pincer lesion – involves excessive overgrowth of the acetabulum resulting in too much coverage of the femoral head and causing impingement where the labrum gets pinched

You can also see a mixed lesion where Cam and Pincer lesions are involved. FAI may lead or contribute to cartilage damage, labral tears, hyperlaxity, sports hernias, low back pain and early arthritis.

The good news is that these patients typically do well post-operatively. Dr. Philipon et al reported in 2007 in the Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. (click here to read the abstract) on 45 professional athletes who underwent arthroscopic management of FAI with an average follow-up of 1.6 years. In this time period 78% of them were able to return to their sport.

Following surgery, weight bearing may be restricted for the first 4 weeks or so to protect the labrum if it is repaired. With a simple debridement and re-contouring of the acetabulum, weight bearing may be initiated earlier. Avoiding twisting motions and excessive external rotation is a must in the first month or so as well. Typically, impact and twisting restrictions are lifted around 3 months post-op.

In the end, proper diagnosis and treatment is necessary to preserve the hip joint and maximize function and return to sport. If you or someone you know suffers from chronic and persistent hip pain that has failed conservative treatment, then consider getting a second look to rule out FAI.