Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

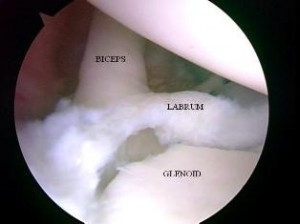

Baseball pitchers who fail nonoperative care for SLAP injuries will undergo a repair if they wish to continue throwing. The injury may occur at ball release as the biceps contracts to resist glenohumeral joint distraction and decelerate elbow extension. The other thought is that injury occurs in late cocking as the result of a “peel back” mechanism when the abducted shoulder externally rotates. Previous research by Shepard et al. published in American Journal of Sports Medicine (AJSM) measured in vitro strength of the biceps-labral complex during the peel back and distal force and concluded that repetitive force in both scenarios likely causes SLAP lesions.

“Baseball pitching motion 2004“. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the concerns for pitchers after surgery is regaining full shoulder external rotation and horizontal abduction. If too much tension is placed on the glenohumeral ligaments during surgery, regaining motion can be tough. Ironically, external rotation is limited in the early phase of rehab to protect the labral repair which may impair throwing mechanics later on. Appropriate rehab and progression is paramount for long term success.

Laughlin et al. at the ASMI sought out to explore in a labaratory if there are differences in pitchers who underwent a SLAP repair compared to those in age controlled groups without injury. In a paper published in the Dec. 2014 AJSM, the researchers hypothesized that the SLAP group would exhibit compromised shoulder range of motion and internal range of motion torque during pitching. Of 634 pitchers (collegiate and professional) tested at ASMI from 2000 – 2014, 13 in this group were included in the SLAP group as they had undergone a SLAP repair at least 1 year before their biomechanical testing.

SLAP tears are a common problem for overhead athletes among others today. There is no consensus per se in how to treat them and results following primary repair are mixed. Common complaints following a repair are persistent pain and stiffness. In the past, I have writtne about SLAP tears as well as outcomes for elite pitchers.

In addition, I have discussed outcomes for type 2 SLAP tear revision surgery on this blog. What always concerns me (and more importantly patients who undergo surgery is how to achieve predictable pain relief and recover shoulder function. In the April 2014 edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine, there is a level 4 prospective study by McCormick et al. looking at the efficacy of subpectoral biceps tenodesis as a viable solution for failed primary SLAP repairs. The study took place from 2006-2010 and all procedures were performed by 2 fellowship trained surgeons at a tertiary military facility.

Subjects: Active-duty men and women b/w 18 and 50 years old who had arthroscopically confirmed type 2 SLAP lesions and who then underwent arthroscopic repair and were subsequently unable to return to duty(follow-up period was 2-6 yeaers with mean follow-up of 3.5 years). They also had to consent to a biceps tenodesis to address the failed repair. All told, 42 of 46 patients completed the study. The mean age was 39.2, while 85% of the subjects were male.

Criteria to be included in the study: inability to return to active duty within a minimum 6 months of surgery, ASES score less than 75 at 1 year follow-up from the primary procedure, or patient electing to undergo revision surgery due to dissatisfaction with the primary results.

Procedure: Biceps tendon was released and the remaining stump was debrided so the superior labrum was confluent with the remaining labral tissue. All sutures and loose anchors were removed. If the rotator cuff interval was inflamed, debridement with a 4.o mm shaver was used and/or radiofrequency wand was used. Next, a 2 cm incision was made in the axillary skin crease at the inferior border of the pec major. The biceps tendon was anchored 1 cm proximal to the musculotendinous junction using a nonabsorbable suture and 8 x 12 interference anchor fixation.

Rehab protocol: Patients were in a sling for 4 weeks with no active biceps use for 6 weeks. They all underwent graded supervised physical therapy consisting of an initial 6-week phase of passive ROM exercise in addition to scapular and core strengthening. This was followed by progressive strengthening at 6 weeks and return to-duty-evaluation at 3 months post-op.

Results

- 34 patients (81%) returned to active duty

- Clinically significant improvement across all outcome measures after revision surgery as follows:

- Pre-op ASES = 68 and post-op ASES = 89

- Pre-op SANE = 64 and post-op SANE = 84

- Pre-op WOSI = 65 and post-op WOSI = 81

- Pre-op shoulder flexion = 135 and post-op shoulder flexion = 155

- Pre-op shoulder abduction = 125 and post-op shoulder abduction = 155

Summary

Currently, there is no standard of care for failed SLAP repairs. One previous case control study by Boileau et al. found higher satisfaction in those undergoing biceps tenodesis compared to arthroscopic repair in the management of an isolated SLAP tear. Further, in the Boileau study there were no failed tenodesis procedures and those opting for that as revision had a full return to previous sports activity. This prospective study by McCormick et al. resulted in similarly high rates of return to previous activity and clinically significant improvements in outcome scores and ROM.

There are several reasons why primary SLAP repairs may fail including: postoperative stiffness as a result inadvertent restriction of physiological biceps excursion or nonanatomic biceps anchor reduction, suture anchor pullout, suture granuloma formation, suture pullout, synovitis, glenoid osteochondrolysis from prominent hardware, a suprascapular nerve injury (due to prominent mendial hardware placement), and a delaminated long head of the biceps.

It is also important to keep in mind the anterior-superior labrum and glenoid are poorly vascularized, and this is thought to limit the healing process. Persistent pain may manifest after surgery in light of the fact the proximal intra-articular portion of the long head of biceps tendon contains sensory and sympathetic fibers associated with shoulder pain. The authors’ findings at the revision procedure in this study suggest a consistent constellation of multifactorial complicating factors including: synovitis of the rotator cuff interval, loose knots, and a lack of healing at the glenoid interface.

Key takeaways

- Outcomes following primary SLAP repairs are inconsistent and patients often continue to c/o persistent pain and stiffness

- Military personnel (an extremely active population) had excellent results with a tenodesis procedure

- The results of this study cannot be generalized to the general public nor overhead athletes per se

- This study did not employ randomization nor did it compare the tenodesis to another procedure/modality so further research should be done on this

- Biceps tenodesis seems to provide a safe and effective treatment option for failed SLAP repairs at a minimum of a 2 year follow-up in active individuals

References

Boileua et al. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

McCormick et al. The efficacy of biceps tenodesis in the treatment of failed superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2014;(42):820-825.

One of the most difficult problems to treat in the clinic is chronic pain related to tendinopathy. More specifically, the Achilles tendon, patella tendon and elbow extensors often present challenges for doctors and clinicians alike when it comes to effectively reducing or resolving pain. Over time, people develop chronic inflammation or even little tears in the muscles running up to the lateral epicondyle.

There have been many studies done looking at PRP over the past 5-10 years. The debate continues, however, with respect to its efficacy in terms of results, especially given the fact that patients must currently pay out of pocket for the procedure. I have written two earlier posts on PRP that you may be interested in reading as a back drop for this one:

2011 – An Update on Platelet Rich Plasma

2011 – Platelet Rich Plasma and Rotator Cuff Repairs

Currently, my approach to treating these injuries involves an approach focused on soft tissue mobilization via instrument assisted soft tissue mobilization, stretching, strengthening and a trial of iontophoresis in most cases. We also offer dry needling at our facility and this has been effective in reducing pain. I will talk more about this point later as it relates to the prospective multi-center trial summarized by Mishra et al. in the February 2014 edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Before I get to the study, I thought it would be pertinent to provide some straightforward information on PRP as it is a question that comes up with patients on a regular basis. Essentially, the process is as follows:

1. Collect 30-60 ml of blood form the patient’s arm

2. Blood is then placed in a centrifuge. The centrifuge spins and separates the platelets from the rest of the blood.

3. A syringe is then used to extract 3-6ml of the platelet-rich plasma

4. The concentrated platelets are then injected into the elbow (or site being treated)

The thought behind PRP is to increase the growth factors up to 8x, which promotes temporary relief and stops inflammation. The question is how successful and cost effective is this process? Consider that opting for surgery will run between $10,000 and $12,000 figuring in costs for the surgeon, hospital/surgery center, anaesthesiologist, etc. PRP injections will cost upwards of $1000, so one would think that would be a favorable option for insurers if surgery could be averted.

What about cortisone injections? They are widely used as a survey of 400 members of the American Academy or Orthopedic Surgeons found that 93% had administered a corticosteroid injection for lateral epicondylar tendinopathy. According to Bisset et al (Br Med J 2006) and Lindhovius et al (J Hand Surg Am 2008) cortisone injections do provide short term pain improvements but also result in a high rate of symptom recurrence. There are other potentially harmful side effects from injections including: reduced collagen synthesis, depletion of human stem cells, depigmentation, and enhancement of fatty and cartilage like tissue changes that can lead to tendon ruptures.

So, the big question is whether or not tendon needling with PRP is an effective treatment option for chronic tennis elbow suffers. Mishra and his colleagues set out to examine this with a double blind, prospective, multi-center randomized controlled trial of 230 patients. In the study, the patients were teated at 12 different facilities over 5 years. All patients had at least 3 months of pain/symptoms and failed conservative treatment.

I have been a bit behind on blogging as of late. I try to aim for one per week, but I also strive to deliver sound and relevant content. Additionally, I do not seek outside contributors so finding time to write can be tricky with work and family life too. So, forgive me for any apparent inconsistency in posting. Just know that I will always try to provide valuable content. Today’s post centers around an article in the July 2012 edition of AJSM.

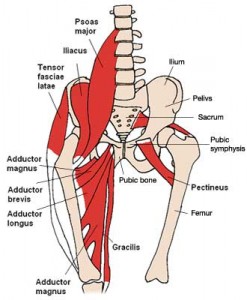

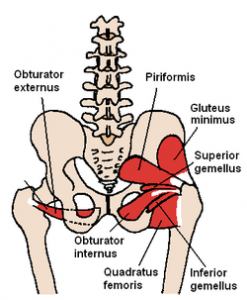

My work at the Athletic Performance Center has provided me an increased opportunity to work with FAI and athletic hip injuries. This is an area of evolution and growth in our field, so I find it particularly interesting to see rationale and thought processes centering around the timing, contribution and selection of hip exercises for active patients/athletes.

This article comes from the Steadman Philippon Research Institute in Vail, CO. The purpose of the study was to measure the highest activation of the piriformis and pectineus muscle during various exercises. The hypothesis was that highest pectineus activation would occur with hip flexion and moderate activity with internal rotation, whereas the highest activation with the piriformis would be with external rotation and/or abduction.

Methods: 10 healthy volunteers completed the following 13 exercises:

- Standing stool hip rotation

- Supine double leg bridge

- Supine single leg bridge

- Supine hip flexion

- Side-lying hip ABD with external rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD with internal rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD against a wall

- Hip clam exercise with hips in 45 degrees of flexion

- Hip clam exercise with hips in neutral

- Prone heel squeeze

- Prone resisted terminal knee extension

- Prone resisted knee flexion

- Prone resisted hip extension

All of these exercises have been reported to be used in hip rehab following arthroscopy or recovery from injury. The exercises were executed slowly and methodically with a metronome to reduce EMG amplitude variations.

Disclaimer: This post is a small rant from me. I normally don’t use this blog as a medium for that purpose. However, I feel so strongly about this topic that I decided to share my thoughts on it.

I had an interesting email exchange with a health care practitioner (HCP) this past week. She had some questions about one of my products and asked specifically if I had done a clinical trial comparing my treatment method to leading national PT organizations. My answer was no.

I explained to her I am not a researcher, nor do I have the time (or money for that matter) for such things as I am in the trenches every day treating patients and training athletes. Her response was very interesting. According to her I was defensive, and she suggested I check out a DPT program so I could in essence become a better clinician.

Hmmm……… Suffice it to say I completely disagree with her on this one. I graduated from PT school at the Ohio State University in 1996. Their program was very well respected at the time (over 500 applied and they took 60 in my class) and two of my professors (Lynn Colby and Carolyn Kisner) wrote the text on Therapeutic Exercise that is still used in many curriculums today. On top of that, I worked at the top outpatient ortho clinic in the city as an aide my junior and senior year in college.

At the time of my admission, OSU only offered a B.S. degree, so I never had a choice for more at that point. The university quickly adopted a Master’s program shortly after I finished and later became one of the first institutions to offer the full DPT program.

Upon graduation, I went to work at the same top ortho clinic and spent 5 years working side-by-side with some of the brightest PT’s and next door to what was considered by many to be the best surgical group in town. I saw surgeries, sat in on MD appointments with my patients, participated in journal clubs and worked at a feverish pace. Let’s just say I saw lots of patients and gained what felt like a fellowship experience for 5 more years.

Now, as I reflect upon this email from said HCP, I can honestly say that I believe experience and results matter more than just those three letters behind a name. That is in no way meant as a slam or any disrespect to the DPTs out there, clinical research trials or the doctorate degree itself. Students today have no choice but to take the DPT route. To be honest, they really only have (1) more year of structured curriculum than I had in my program. They leave school with a lot more debt, and afterward they still have no clinical (real world) experience when they first start out. You simply can’t buy experience in school.