Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

Rotator cuff tears are common injuries, especially among active middle age men. As researchers and scientists seek for better ways to promote healing and more optimal surgical outcomes, PRP continues to get lots of attention. If you want a basic primer on PRP, click here to read one of my earlier posts on it.

In a recent study in the October 2011 American Journal of Sports Medicine, researchers looked at the effects of PRP on patients undergoing surgery for full thickness rotator cuff tears. This is the first prospective cohort-control study to investigate the effect of PRP gel augmentation during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Forty two patients were included in the study (average age of 60), with 19 undergoing arthroscopic repair with PRP and 23 without.

Outcomes were assessed preoperatively and at 3, 6, 12, and finally at a minimum of 16 months after surgery (at an average of 19.7 +/- 1.9 months) with respect to pain, range of motion, strength, and overall satisfaction, and with respect to functional scores as determined using multiple assessment tools. At a minimum of 9 months after surgery, repaired tendon structural integrities were assessed by magnetic resonance imaging.

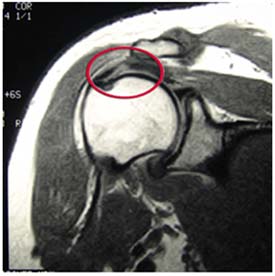

Below are images defining a full thickness rotator cuff tear:

Partial (left) vs. Full (right)

Full Thickness Tear on MRI

In my practice, I take care of many athletes ranging in age from 10 and up. Many of the injuries I see are related to over training and overuse. Common things I see in the clinic on a daily basis include but are not limited to:

- Tendonitis

- Shin splints

- IT Band Syndrome

- Patellofemoral pain

- AC joint pain/arthritis

The list can go on and on. There are many factors (inherent and training related) that contribute to such problems. I personally believe many problems can be prevented with better education, smarter training, coaching predicated on individuality and physical response, and of course adding in more recovery. Cross training is also a must – just look at what sport specialization at an early age has done to current injury rates.

You need not look any further than the declining age of patients walking through the door with what I term “repetitive microtrauma” injuries. I saw a 14 year old cross country female runner a few weeks ago who had her second stress reaction injury inside of 12 months. In addition, the rise in the number of Tommy John surgeries performed in the past decade with respect to those having them at an earlier age may serve as a harsh warning sign about doing too much too soon or doing too much of the same thing year round.

I say all this simply to say we must not be oblivious to the rise in these types of mechanical injuries. Throwing, swimming, and running are all activities that become dangerous if done in excess, and they also produce predictable injury patterns. So, if you are curious about some risk factors and how to better balance your training and manage these types of injuries, then check out a webinar I just did for Raleigh Orthopaedic Clinic last week (click on the screen shot below to view the webinar)

This presentation is ideal for athletes, parents, weekend warriors and sports coaches looking for practical, straightforward information on this topic with some foundational guidelines that can be applied objectively and immediately to injury management and recovery. If this information helps just one person avoid an injury or accelerate their recovery then I will be thrilled! Please feel free to forward this post to friends, share it on FB or tweet it!

One of the greatest things about medicine is that it continues to evolve and change. Sports medicine is at the forefront and athletes are always looking for faster ways to recover and get back in the game. If you are not familiar with platelet rich plasma (PRP) therapy, click here to read my earlier post on it.

It has been used increasingly to treat muscle strains and chronic tendinitis in the heel, knee and elbow. While some early responses have been favorable, there has not been much follow-up data or research available to assess its efficacy. In the August edition of the American Journal of Sports Medicine reports on one-year follow-up for the use of PRP in chronic Achilles tendinopathy.

The study was a double blind randomized placebo-controlled study using 54 patients (age 18-70) who had chronic tendinopathy 2-7 cm proximal to the Achilles tendon insertion (minimum of 2 months). They were randomized and given PRP or a saline injection in addition to an eccentric training program. Keep in mind recent research has indicated the efficacy of eccentric training to treat chronic tendon problems.

In this intervention, patients were given the injection with ultrasonagraphic guidance. After the injection, theyw ere told to avoid sports for 4 weeks. In week 2, they preformed a stretching program. Then all participants began a 12 week eccentric exercise program. Follow-up was done at 6, 12 and 24 weeks by one researcher, while another blinded researcher did the one-year follow-up. Clinical and ultrasonagraphic follow-up was done at each interval.

Results

At the 1 year follow-up, there was no clinical or sonagraphic benefit of PRP. This matches the findings at 6 months as well. One other radnomized studly looking at tennis elbow did find a statistical significance when they compared PRP to a corticosteroid injection at 1 year, instead of a placebo injection. Another key factor or difference is one area is load bearing and the other is not.

In reviewing this study, it should be noted that not only was pain reduction not statistically greater, nor was there any added positive tendon structure changes noted using the PRP. With that said, the looming issue with this treatment intervention is that variables like platelet count, injected volume. number of injections, preactivation and the presence of leukocytes are not always the same across studies, and they were not determined within this study either.

The takeaway here is that there appears to be no added benefit from PRP with chronic Achilles tendinits. However, there is no known negative side effect associated with trying it either. I think the hardest part is scaling back activity and being patient enough to overcome these injuries. In my experience, they often require soft tissue massage, rolling, stretching, eccentric loading, relative rest, and a very specific return-to-activity plan based 100% on the tissue and pain response of the patient.

Time and future research will continue to tell us more about PRP. I think we may find that different growth factors and treatment options may evolve that do in fact speed regeneration and healing.

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is often a hidden and misunderstood cause of hip pain. I currently work with a physician who has studied under some of the best hip arthroscopists in the US, and he is performing arthroscopic procedures to resolve hip impingement. For many years, this has likely been a source of misdiagnosed, under treated and debilitating hip pain for people.

As things advance in medicine, hip arthroscopy is expanding and allowing for easier surgical correction of these issues. However, it is not an easy surgery technically speaking. As such, finding the right surgeon (if needed) is critical to attaining a positive outcome. Who normally gets it? Unfortunately, many people are predisposed to it, much like we see the natural genetic architecture (shape) of the acromion affecting impingement in the shoulder.

If you have an overhang of the hip acetabulum (socket) or non-spherical shape of the femoral head (or both) this can compromise the joint space and injure the joint cartilage and/or labrum. Destruction can occur at a very young age. I am currently rehabbing a 19 y/o male who recently underwent hip arthroscopy to debride his labrum and smooth out the hip socket and re-shape the femoral head. He had extensive damage at an early age due to his joint architecture and shows some signs of impingement on the other side as well.

How do you know if you have hip impingement? Generally, you may have hip joint pain along the front, side or back of the hip along with stiffness or a marked loss of motion (namely internal rotation). It is common in high level athletes and active individuals. However, other things may cause hip pain as well such as iliopsoas tendonitis, low back pain, SI joint pain, groin strain, hip dysplasia, etc. so a careful history, exam and plain films are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. If suspected, an MR athrogram is usually ordered to confirm if there are labral tears present. Physicians also use an injection with anesthetic to see if the pain is truly coming from the hip joint. This may be done under fluoroscopy to ensure it is in the joint space.

Signs and symptoms of FAI may include:

- Pain with sitting

- Pain or limited squatting

- Stiffness and decreased internal rotation

- Pain with impingement testing (see picture below of hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation – examiner will move the hip into this position and marked stiffness/loss of internal rotation and pain indicates a positive test)

Conservative treatment typically involves limiting or avoiding squats, strengthening the core and hip stabilizers as well as attempting to maximize mobility of the joint. Due to the fact that by the time pain brings patients in to see the doctor there has already been marked labral and joint damage, a cautious and proactive approach to managing hip pain is warranted especially in younger active patients and athletes.

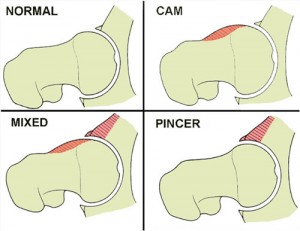

The types of lesions seen are either Cam or Pincer lesions.

Cam lesion – involves an aspherical shape of the femoral that causes abnormal contact between the ball and socket leading to impingement

Pincer lesion – involves excessive overgrowth of the acetabulum resulting in too much coverage of the femoral head and causing impingement where the labrum gets pinched

You can also see a mixed lesion where Cam and Pincer lesions are involved. FAI may lead or contribute to cartilage damage, labral tears, hyperlaxity, sports hernias, low back pain and early arthritis.

The good news is that these patients typically do well post-operatively. Dr. Philipon et al reported in 2007 in the Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. (click here to read the abstract) on 45 professional athletes who underwent arthroscopic management of FAI with an average follow-up of 1.6 years. In this time period 78% of them were able to return to their sport.

Following surgery, weight bearing may be restricted for the first 4 weeks or so to protect the labrum if it is repaired. With a simple debridement and re-contouring of the acetabulum, weight bearing may be initiated earlier. Avoiding twisting motions and excessive external rotation is a must in the first month or so as well. Typically, impact and twisting restrictions are lifted around 3 months post-op.

In the end, proper diagnosis and treatment is necessary to preserve the hip joint and maximize function and return to sport. If you or someone you know suffers from chronic and persistent hip pain that has failed conservative treatment, then consider getting a second look to rule out FAI.

By far the most comments on my blog and emails that flood my inbox these days have to do with SLAP tears. I must admit that outside of ACL tears and rotator cuff issues, I find myself increasingly drawn to studying and researching this issue. It definitely is a source of great pain for many and an issue that medical professionals are challenged by today.

In my personal clinical experience, I see good, bad and in between outcomes. Through email and my blog I tend to read more on the not so good side from people who are seeking my expertise in how to resolve their issues. When I speak to surgeons, I find they are often hesitant to commit to a set algorithm of treatment, and they are not 100% sure what the right answer is in addressing these injuries as a whole.

If you read the literature, the success in terms of patient satisfaction and return to premorbid activity levels is not going to make you rush down to the operating room and opt for an arthroscopic repair if you are an overhead athlete (especially baseball players). However, other studies have presented more favorable data ranging from 63%-75% good-excellent satisfaction in other overhead athletes who have had the procedure done.

If you are unfamiliar with SLAP tears, I suggest reading my original post on them (click here). In today’s post, I wanted to present a quick recap on Type II SLAP tears and some new published research on the results of revision procedures where the primary repair failed.

Below are two images of a type II tear (MRI and operative view from the scope)

Keep in mind a type II tear means the biceps anchor/superior labrum has pulled away from the glenoid with resulting instability of the complex. This is the most common type of tear seen among injured people. In a study from the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in LA in the latest American Journal of Sports Medicine (June 2011 – click here for the abstract), they discussed a chart review of from 2003-2009 looking at patients who had undergone revision type II SLAP repairs.