Brian Schiff’s Blog

Injury Prevention, Sports Rehab & Performance Training Expert

I have been a bit behind on blogging as of late. I try to aim for one per week, but I also strive to deliver sound and relevant content. Additionally, I do not seek outside contributors so finding time to write can be tricky with work and family life too. So, forgive me for any apparent inconsistency in posting. Just know that I will always try to provide valuable content. Today’s post centers around an article in the July 2012 edition of AJSM.

My work at the Athletic Performance Center has provided me an increased opportunity to work with FAI and athletic hip injuries. This is an area of evolution and growth in our field, so I find it particularly interesting to see rationale and thought processes centering around the timing, contribution and selection of hip exercises for active patients/athletes.

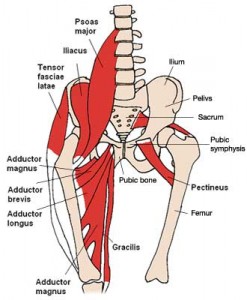

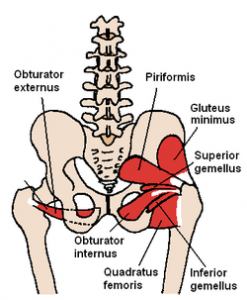

This article comes from the Steadman Philippon Research Institute in Vail, CO. The purpose of the study was to measure the highest activation of the piriformis and pectineus muscle during various exercises. The hypothesis was that highest pectineus activation would occur with hip flexion and moderate activity with internal rotation, whereas the highest activation with the piriformis would be with external rotation and/or abduction.

Methods: 10 healthy volunteers completed the following 13 exercises:

- Standing stool hip rotation

- Supine double leg bridge

- Supine single leg bridge

- Supine hip flexion

- Side-lying hip ABD with external rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD with internal rotation

- Side-lying hip ABD against a wall

- Hip clam exercise with hips in 45 degrees of flexion

- Hip clam exercise with hips in neutral

- Prone heel squeeze

- Prone resisted terminal knee extension

- Prone resisted knee flexion

- Prone resisted hip extension

All of these exercises have been reported to be used in hip rehab following arthroscopy or recovery from injury. The exercises were executed slowly and methodically with a metronome to reduce EMG amplitude variations.

There seems to be consistent questions, debate and studies done with respect to stretching. As the thought of more closely analyzing the quality of movement (FMS, Y-Balance testing, SFMA for example) moves to the forefront in the PT and fitness world, many search for the right mix of exercise to maximize mobility.

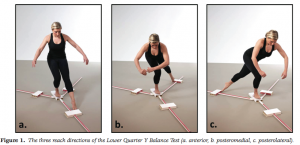

I count myself as a supporter and follower of the work of Gray Cook and Stuart McGill. While I may not agree 100% with all of their ideas, I generally consider them to be brilliant minds and ahead of the curve. I have been using the FMS in my practice for some time now and have also begun to incorporate Y-Balance testing as well (see pic below courtesy of the IJSPT)

The Y-Balance test may not have significant relevance to hip mobility as much as it does limb symmetry, but I included it here to illustrate my point in observing kinetic chain movement to help determine where the weak link or faulty movement pattern may be. It gives us valuable information with respect to strength, balance and mobility.

With the revelation that FAI is more prevalent than we knew (click here for my post on FAI), I am always interested in hip mobility and how to increase movement in the hip joint. Limitations in hip mobility can spell serious trouble for the lumbosacral region as well as the knee.

I currently use foam rolling, manual techniques, dynamic warm-up maneuvers, bodyweight single leg and hip/core disassociation exercises and static stretching to increase hip mobility. However, I am often faced with the question of what works best? Is less more? How can I make the greatest change without adding extra work and unnecessary steps?

Well, Stuart McGill and Janice Moreside just published a study in the May 2012 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research that sought to examine three different interventions and how they improve hip joint range of motion. Previous work has been focused on the hip joint alone, and they wanted to see how other interventions impacted the mobility of the hip. Click here for the abstract

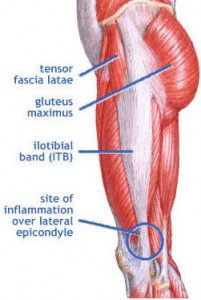

So, a very common issue I see in runners is iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome. In a nutshell, it involves excessive rubbing or friction of the ITB along the greater trochanter or lateral femoral epicondyle. It is more common along the lower leg just above the knee and typically worsens with increasing mileage or stairs.

The ITB is essential for stabilizing the knee during running. Several factors may contribute to increased risk for this problem:

- Muscle imbalances (weak gluteus medius and deep hip external rotators)

- Uneven leg length

- High and low arches

- Increased pronation leading to excessive tibial rotation = friction of the band

- Improper training progression

- Faulty footwear

- Poor running mechanics

- Limited ankle mobility (specifically dorsiflexion)

- Tightness in the tensor fascia latae (TFL) and glute max

Related information on this topic include a 2010 study published in JOSPT on competitive female runners with ITB syndrome:

Click here to see the abstract of the study

Click here to read an earlier blog post analysis of the above research article

Common signs and symptoms include stinging or nagging lateral knee pain that worsens with continued running. Hills and stairs may further aggravate symptoms. Some runners even note a “locking up” sensation that forces them to stop running altogether. How do I treat this?

It is widely accepted that decreased hip strength and stability leads to knee valgus. Excessive frontal plane motion and valgus torque increase the risk for non-contact ACL injuries. While we know that hip abductor weakness is more of an issue in females than males, the question remains to what degree other factors are involved.

Claiborne et al (1) noted that only 22% of knee variability could be linked solely to hip muscles surrounding the hip. In light of this we must look at the whole kinetic chain when assessing movement dysfunction and injury risk. In the most recent issue of the IJSPT, researchers sought to discover how activating the core during a single leg squat would impact the kinematics of 14 female college-age women. They excluded participants with current pain or injury to the lower extremities or torso, or if they had a history of any lower extremity injuries or surgeries in the past 12 months.

The participants were assessed for their capacity to recruit core stabilizer muscles using lower abdominal strength assessment as described by Sahrman (2). This testing model has 5 levels of increasing difficulty used to challenge participants to maintain a neutral spine. The draw back of this method is that it is done in supine versus the standing position of this study, but the author acknowledges this limitation. Out of a possible high score of 5, five of the participants scored a 1 or 2, while the other nine scored a zero.

For the study, a six inch step was used to assess 2 reps of a single leg squat. Each participant was asked to perform the test with the dominant leg to standardize conditions. They performed the reps under two conditions:

1. CORE – engaged abdominal muscles as they had been instructed to do so during the Sahrman test

2. NOCORE – no purposeful engagement of abdominal muscles

Results

- The CORE condition resulted in smaller hip displacements in the frontal plane but had no effect on hip angular range of motion – essentially there was less medial/lateral movement

- The CORE group did not exhibit any changes in knee displacement but did exhibit greater degree of knee flexion – this may suggest higher function assuming more knee flexion is desired during squat tasks in sports and functional activities

- Those scoring the lowest on the core assessments had larger improvements in performance when they did in fact activate the core musculature

How do we use this information to affect our practice? Well, in terms of rehab it seems straightforward and many of us may already encourage patients to activate their core during treatment. However, I think the greater contribution may come in injury prevention programs (particularly ACL programs) where we are looking at all facets of neuromuscular control and appropriate muscle activation patterns.

With any prehab or rehab strategy, we as clinicians, trainers and strength coaches are essentially trying to reprogram the brain to summon and execute a better motor pattern or strategy – feedforward training. We know that healthy individuals tend to have better transverse abdominus and multifidus muscle activation, so it only makes sense to consider activation of local stabilizers as we work on global muscles. Improving core and pelvic stability should only help reduce unwanted frontal plane motion.

With that said, the authors of this study readily acknowledge more work needs to be done with larger clinical populations (including EMG work) to more clearly identify what magnitude the core musculature has on lower extremity motion and displacement.

Keep in mind the proper program will always stem from your ability to assess movement impairment and tissue dysfunction. I suggest beginning with a FMS in the athletic population and incorporating parts of that or the SFMA to compliment your evaluation in the clinic. This will generally reveal the priorities for the corrective exercises. For now, we can use this information in this particular study to be more intentional with our patients and clients suffering knee and hip dysfunction by adding this one simple step to our programming.

References

1. Claiborne TL, Armstrong CW, Gandhi V, Princivero DM. Relationship between hip and knee strength and knee valgus during a single leg squat. Journal of applied biomechanics. 2006;22(1):41.

2. Faries MD, Greenwood M. Core training: stabilizing the confusion. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2007 ;29(2):10.

Research has shown that strengthening the gluteus medius is clearly an essential way to reduce anterior knee pain and improve pelvic stability and function. The exercise I am sharing today is useful for improving hip strength and pelvic stability in a closed chain fashion.

In the video below, I demonstrate a very effective way to strengthen the gluteus medius and improve hip stability.

For a full description of the exercise, check out my latest column, Functionally Fit, by clicking here.